Table of Contents

Every executive knows the scene. Ten brilliant people sit around a polished table, nodding in unison like synchronized swimmers. The smartest person spoke first, and now everyone agrees. The decision gets made in twenty minutes. Everyone leaves feeling efficient. Six months later, the initiative crashes spectacularly, and those same ten people wonder how they all missed the obvious warning signs.

This is groupthink, and it ruins more companies than any external competitor ever could.

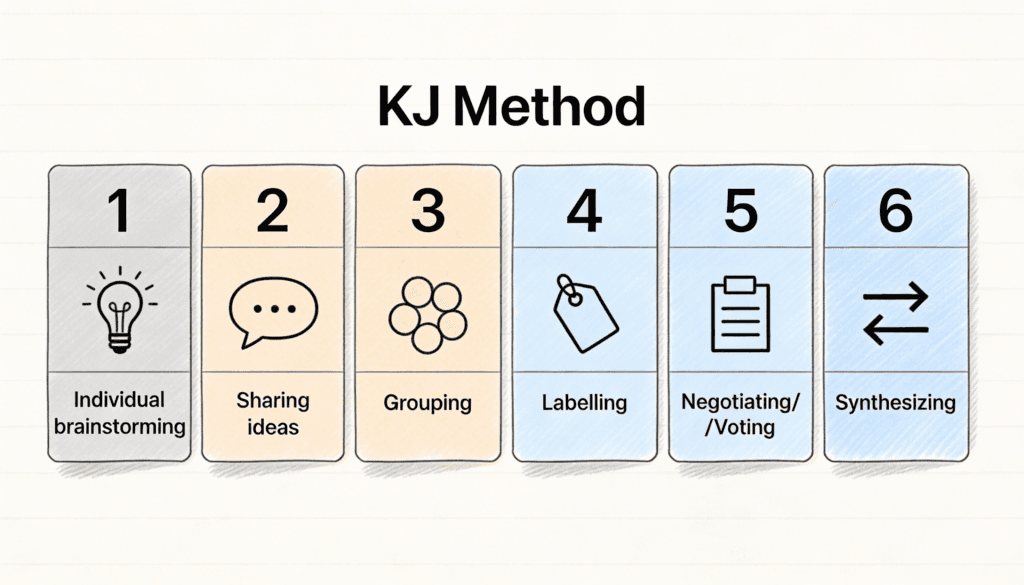

The KJ Method, developed by Japanese anthropologist Jiro Kawakita in the 1960s, offers a peculiar antidote. Unlike most brainstorming techniques that claim to prevent groupthink while actually just rearranging the furniture, the KJ Method restructures how groups collect, organize, and synthesize information. It does something rare in corporate settings: it makes disagreement easier than agreement.

The Silent Rebellion: Why Writing Comes Before Talking

The first way the KJ Method disrupts groupthink is almost absurdly simple. Everyone writes their observations and ideas on cards before anyone speaks.

Think about standard meetings. The CEO shares his perspective. The CFO builds on it. The VP of Marketing, who actually disagreed, now faces a choice: challenge two senior executives publicly or find a way to frame his concerns that sounds supportive. Most people choose survival over truth.

The KJ Method reverses this power dynamic. When you write your observation on a card before the hierarchy asserts itself, you’ve already committed. Your idea exists physically in the world. It’s much harder to pretend you never thought the strategy was flawed when your handwriting says otherwise on a card sitting in front of everyone.

This connects to something psychologists discovered about accountability. When people make private predictions, they’re far more accurate than when they make public ones. Public prediction gets contaminated by social desirability. You predict what makes you look good, not what you actually believe. The KJ Method creates a brief window where ideas emerge private, then become public only after they’re externalized.

But here’s the counterintuitive part: writing first doesn’t just protect dissenters. It protects the person who spoke the popular opinion from seeming like a dictator. When the CEO’s idea appears on a card alongside seventeen others, it’s just another data point. The power dynamic temporarily suspends. Everyone becomes a contributor rather than a supplicant.

The Democracy of Data: One Idea Per Card

The second mechanism is the constraint itself. One observation, one card.

This seems like a formatting preference, but it’s actually a profound philosophical stance about how ideas relate to power. In normal meetings, articulate people dominate by packaging multiple ideas together in compelling narratives. They tell stories. They connect dots. They create momentum that carries people along.

The KJ Method strips this advantage away. Your eloquence doesn’t matter when you can only write seven words on a sticky note. The shy analyst who noticed a troubling pattern in customer complaints has the same real estate as the charismatic SVP who wants to expand into a new market. Each observation stands alone, naked of rhetoric.

This relates to what information theorists call chunking. When we package ideas together, we create meaning but we also create bias. The person who says “Our customers love the product but hate the service, which means we should invest in training” has smuggled a conclusion into their observation. They’ve chunked three separate ideas together: customer product satisfaction, customer service dissatisfaction, and a proposed solution.

The KJ Method forces decomposition. Those become three cards. Maybe four. And once they’re separated, other people might see different patterns. Maybe the customers who love the product are different customers from those who hate the service. Maybe the service problems stem from product complexity, not training. The conclusion that seemed obvious when packaged together becomes questionable when examined as components.

This is why totalitarian regimes fear archives and libraries. When you can examine individual facts separate from the narrative that surrounds them, you might notice the narrative doesn’t actually fit the facts.

The Wisdom of Crowds Hiding in Plain Sight

The third way the KJ Method prevents groupthink is through affinity grouping, which sounds boring but contains a profound insight about collective intelligence.

After everyone writes their cards, the group silently sorts them into clusters based on natural affinity. Cards that seem related go together. No one explains their sorting logic. No one defends their groupings. People just move cards around until patterns emerge.

Here’s what makes this powerful: the group discovers its own categories rather than having them imposed from above.

Traditional analysis starts with predetermined buckets. Management consultants arrive with their frameworks: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats. Or: people, process, technology. These frameworks aren’t wrong, but they’re limiting. They tell you where to look before you know what you’re looking for.

The KJ Method inverts this. The categories emerge from the data. And this matters because groupthink often happens at the category level, not the observation level. Everyone might agree on the individual facts while completely disagreeing on how to organize them.

Imagine a retail company analyzing declining sales. One executive sees the cards and groups them into “marketing problems,” “product problems,” and “competitive problems.” Another executive takes the same cards and groups them into “urban market challenges,” “suburban market challenges,” and “online market challenges.” Same facts, completely different strategic implications.

When the group sorts together, these competing mental models collide. The marketing VP moves a card about Instagram engagement into the “marketing” pile. The digital director moves it into “urban market.” They both pause. Neither has to explain. They just see that this one fact connects to multiple patterns. The disagreement becomes visible without anyone getting defensive.

This mirrors how Wikipedia prevents ideological capture better than traditional encyclopedias. When anyone can edit and reorganize, extreme positions get moderated not through argument but through continuous rearrangement. The structure itself resists capture by any single perspective.

Labels as Collaborative Sense-Making

The fourth mechanism happens when the group creates labels for their clusters. This seems clerical, but it’s actually where groupthink most often gets dismantled.

Each cluster of cards needs a name. The group has to agree on a short phrase that captures the essence of that cluster. And here’s the trap that prevents groupthink: you can’t agree on a label unless you actually agree on what the cluster means.

In regular meetings, people nod along to vague statements. “We need to focus on customer experience” gets unanimous agreement because everyone defines customer experience differently. The VP of Technology thinks it means better software. The VP of Service thinks it means more empathetic support agents. They agree on words while disagreeing on everything that matters.

The KJ Method makes this impossible. When you have twelve cards about customer complaints in front of you, and you need to label that cluster, the disagreement becomes unavoidable. Someone suggests “Product Quality Issues.” Someone else says “Mismatch Between Expectations and Reality.” Those aren’t the same thing at all. One implies fixing defects. The other implies managing promises.

The group has to negotiate. They have to look at the actual cards and ask: what do these really say? And in that negotiation, the person with the minority perspective gets leverage. They can point to specific cards. “Look, three of these complaints mention the marketing materials. This isn’t just about quality.”

This connects to linguistics and the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the idea that language shapes thought. When you force a group to negotiate language, you force them to negotiate reality. The labels become a collaborative sense-making exercise that prevents any single perspective from dominating.

The Spatial Arrangement of Disagreement

The fifth mechanism is perhaps the subtlest. The KJ Method happens in physical space, and that spatial arrangement prevents groupthink in ways that abstract discussion never could.

When you arrange cards on a table, you create a shared external representation of the problem. Everyone looks at the same physical object from their different vantage points. This seems trivial until you compare it to how strategic discussions usually happen.

In typical meetings, the problem exists only in language and imagination. I describe my view of the market. You describe yours. We’re both creating mental models, but those models stay trapped in our individual heads. We use metaphors to bridge the gap, but metaphors are slippery. When I say the market is “saturated,” I might mean we can’t acquire new customers profitably. When you hear “saturated,” you might think we can’t grow at all. We agree on the word while disagreeing on the reality.

The KJ Method externalizes all this. The market isn’t an abstraction we argue about. It’s represented by forty-seven cards on a table, organized into seven clusters. When we disagree, we point to physical objects. “I think these five cards about pricing belong with the competitive cluster, not the customer cluster.” Now we’re not arguing about abstract market conditions. We’re arguing about whether specific observations pattern together.

This relates to how architects use physical models. You can argue endlessly about whether a building feels welcoming. But when you put a physical model on the table, suddenly everyone points to the same entrance and says “that’s too small” or “that’s imposing.” The disagreement becomes concrete rather than abstract.

The spatial element also prevents temporal dominance. In regular meetings, whoever speaks last often wins. Recency bias makes the final argument feel most compelling. But when all the ideas exist simultaneously on a table, recency disappears. The first observation and the last observation have equal visual presence. Time flattens into space.

Why Physical Beats Digital

There’s an irony here worth examining. We live in an age of collaborative software and virtual whiteboards. Yet the KJ Method works best with actual paper cards on an actual table.

Digital tools reintroduce hierarchy through their affordances. Someone has to create the virtual workspace. Someone controls the screen share. Someone decides which digital whiteboard software to use, and that choice determines what’s possible. Miro works differently from Mural works differently from a Google Doc.

Physical cards have no features to master. No one gets excluded because they don’t know the shortcuts. The learning curve is zero. And that accessibility matters for preventing groupthink, because groupthink often happens when some people feel too intimidated to participate fully.

This isn’t a Luddite argument against technology. It’s a recognition that different tools create different power dynamics. Video calls create groupthink because you can see who speaks first and who gets interrupted. Chat systems create groupthink because quick typers dominate. Physical cards, arranged on a table where everyone can reach them equally, distribute power more evenly than any digital tool yet invented.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Efficiency

Here’s what makes executives uncomfortable about the KJ Method: it takes longer than groupthink.

You can achieve false consensus in twenty minutes. Real understanding might take three hours. In a world obsessed with efficiency, that feels like a failure. But this reveals a profound confusion about what efficiency means.

Groupthink is efficient at making decisions. It’s catastrophically inefficient at making good decisions. When your twenty-minute meeting produces a strategy that fails six months later, you haven’t saved time. You’ve wasted six months plus the twenty minutes.

The KJ Method trades upfront time for better outcomes. It’s inefficient at consensus building but efficient at truth seeking. And truth seeking prevents the expensive disasters that come from comfortable lies.

This connects to the difference between complicated and complex problems. Complicated problems, like building a bridge, benefit from efficiency. You know what good looks like. You have proven methods. Speed matters.

Complex problems, like strategy in uncertain markets, punish efficiency. You don’t know what good looks like. Your proven methods might be obsolete. Speed just gets you to the wrong answer faster.

The KJ Method recognizes that executive decision making is almost always complex. It slows groups down deliberately because speed is the enemy of seeing clearly.

When Smart People Become Dumb Together

The deepest insight from the KJ Method isn’t about facilitation techniques. It’s about the nature of intelligence itself.

We assume that groups of smart people make smart decisions. But intelligence doesn’t aggregate the way we think it does. Ten people with IQs of 130 don’t create a super-intelligence with an IQ of 1300. They create something that’s often dumber than any individual member.

This happens because social dynamics interfere with cognition. Your brain’s threat detection system treats social rejection as seriously as physical danger. Disagreeing with your boss triggers the same neural pathways as seeing a predator. Your intelligence gets hijacked by your need for belonging.

The KJ Method works because it hacks these social dynamics. Writing before speaking, one idea per card, silent sorting, collaborative labeling, physical arrangement. Each of these disrupts a different mechanism that makes groups dumb.

It doesn’t eliminate social dynamics. That would require eliminating humans. But it channels those dynamics toward truth-seeking rather than consensus-seeking. And that small redirection makes the difference between a group that’s dumber than its members and a group that’s smarter.

The question isn’t whether your executive team is smart enough. The question is whether your decision-making process lets that intelligence function or suppresses it. Most corporate processes suppress it systematically while claiming to enhance it.

The KJ Method offers an alternative. It’s not a perfect tool. It can’t fix organizational cultures that punish dissent or reward yes-men. But it creates spaces where disagreement becomes easier than agreement, where minority views get the same space as majority views, and where patterns emerge from observation rather than authority.

That’s not just a better meeting. It’s a different way of thinking together.