Table of Contents

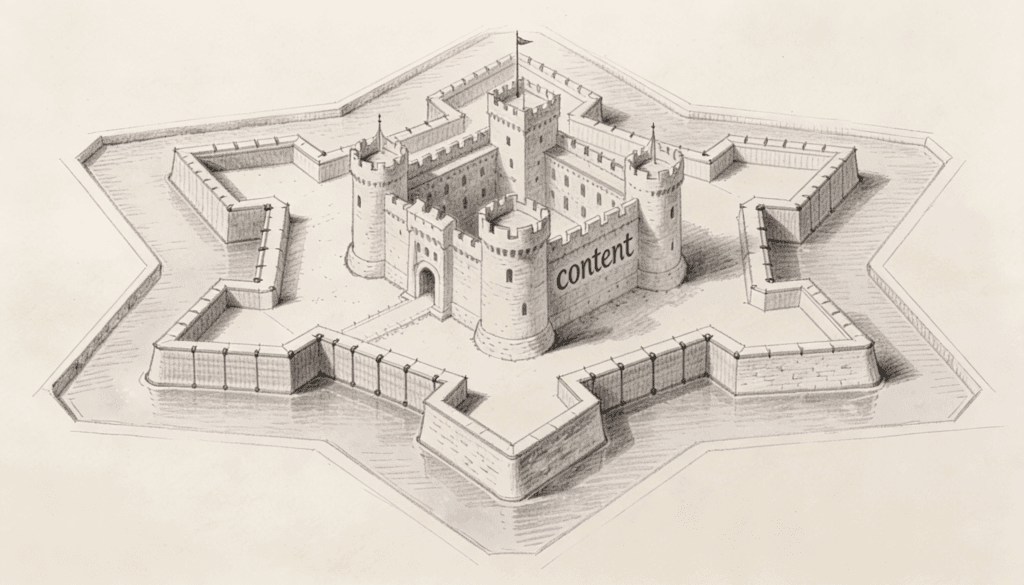

Warren Buffett talks about moats in business. He means the competitive advantages that keep rivals at bay, the things that make a company hard to copy or compete with. The metaphor works because medieval castles with moats were annoying to attack. You could see the castle, you knew what it was, but getting there meant crossing water designed to stop you.

Content strategy needs the same thing. Everyone can see what good content looks like. Everyone has access to the same tools, the same platforms, the same AI writing assistants. The question isn’t whether you can create content. The question is whether you can create something others can’t easily replicate when they decide to compete for the same attention you’re fighting for.

The irony is that most content moats aren’t built by doing more of what everyone else does. They’re built by making choices that seem inefficient at first.

The Problem With Being Replicable

There’s a trap in content creation that feels productive but leads nowhere. You identify keywords, you create optimized articles, you publish consistently, you promote on social media. You do everything the playbooks tell you to do. And it works, sort of. You get traffic. You get engagement.

Then a competitor shows up with a bigger budget or more time. They hire writers, they follow the same playbook, and suddenly your advantage evaporates. What you built wasn’t a moat. It was a sandcastle at high tide.

The fundamental issue is that tactics are easy to copy. Formats are easy to copy. Topics are easy to copy. Even quality, past a certain threshold, becomes a commodity. If your entire strategy can be summarized as “we publish better blog posts about X,” you don’t have a moat. You have a head start that’s rapidly disappearing.

This is where most content strategies stall. They confuse execution with differentiation. Executing well matters, but it’s table stakes. A moat is what remains when everyone else is also executing well.

What Actually Creates Defensibility

Real moats in content come from things that compound over time and can’t be shortcutted. They come from structural advantages, not tactical ones.

The first and most powerful moat is proprietary insight. This means you know things others don’t because of your position, your data, your experience, or your access. A cybersecurity company writing about threats they’ve observed in their own network has a moat. A consultant writing about patterns they’ve seen across dozens of client engagements has a moat. Someone writing generic advice from internet research has no moat.

Proprietary insight can’t be faked. You either have the data or you don’t. You either have the experience or you don’t. When readers recognize that you’re sharing something they can’t get elsewhere, they return. More importantly, competitors can’t simply hire better writers to catch up. They’d need to replicate your entire operation.

The second moat is a distinctive point of view. This is different from having opinions. Everyone has opinions. A point of view is a consistent lens through which you interpret information. It’s a framework that you apply repeatedly, that shapes how you see problems and solutions.

Think about how certain writers or publications become associated with particular ways of thinking. You read them not just for information but because you want to see how they’ll analyze something. That lens becomes valuable in itself. It creates anticipation. When a new topic emerges, readers wonder what that particular voice will say about it.

Building a point of view requires intellectual courage. It means making arguments that not everyone will agree with. It means being willing to zig when the industry zags. Most content plays it safe because safe feels smart. But safe content blends into the background. It gets consumed and forgotten.

The third moat is relationships at scale. This sounds obvious until you realize how few content operations actually build it. Publishing content and hoping people find it isn’t building relationships. Building relationships means your audience feels connected to you, talks back to you, and shares not just your content but their own experiences with you.

When you have real relationships, your content gets better because you’re learning directly from the people you’re trying to reach. You’re not guessing at pain points. You’re hearing them. And when you publish something new, you’re not starting from zero visibility. You have people who care enough to pay attention.

This compounds viciously in your favor. Each piece of content strengthens relationships, which improves the next piece of content, which strengthens relationships further. A new competitor can’t replicate two years of conversation and trust in two months of publishing.

The Counterintuitive Path to Differentiation

Here’s where it gets interesting. The way to build these moats often contradicts standard content marketing advice.

Standard advice says to cover all the important topics in your space. Cast a wide net. Be comprehensive. The moat building approach says to ignore most topics and go absurdly deep on a few. Become the definitive source on something specific rather than an adequate source on everything.

This feels risky. You’re deliberately limiting your scope. You’re turning away potential traffic from topics you’re choosing not to cover. But depth creates authority in a way breadth never does. When someone needs serious help with the thing you’ve specialized in, they come to you. When they need surface level information about adjacent topics, they go to Wikipedia. You don’t want Wikipedia’s job.

Standard advice says to publish consistently on a schedule. The moat building approach says that consistency matters less than memorability. One piece of content that spreads everywhere and changes how people think is worth more than fifty pieces that get polite nods and scroll bys.

This doesn’t mean publishing randomly. It means being willing to hold back decent content while you work on great content. It means sometimes breaking your own publishing schedule because what you’re working on isn’t ready yet and shipping it half baked would do more harm than good.

Standard advice says to optimize for search engines. The moat building approach says to optimize for being cited. When other creators reference your work, when they link to you as a source, when they say “as X pointed out,” that’s a moat. Search algorithms change. Being the source that other sources point to is more durable.

Getting cited requires saying things worth citing. That usually means primary research, original frameworks, or arguments that advance a conversation rather than summarize it. It means creating the content that ends up in other people’s bibliographies.

The Network Effect Inside Your Content

There’s a structural element to moats that doesn’t get discussed enough. Individual pieces of content can reference and build on each other in ways that create compounding value.

When you write about a topic and introduce a framework, then use that framework in subsequent pieces, you’re training readers in a language. That language becomes a barrier to entry for competitors. New readers who encounter your content for the first time and see references to concepts you’ve established have an incentive to explore your archive. They want to understand the references. They want the full picture.

This is different from a content hub or a pillar page strategy. Those are organizational tactics. What I’m describing is intellectual architecture. You’re building a body of work where later pieces assume knowledge of earlier pieces, where ideas evolve and develop over time, where there’s a actual progression of thought.

Doing this well requires planning. You need to think about your content program not as individual articles but as chapters in a longer argument. What idea are you introducing now that you’ll build on later? What terminology are you establishing that will become shorthand for complex concepts?

The payoff is that your content becomes harder to compete with over time rather than easier. A new entrant might match your quality on any single piece, but they can’t match the depth and interconnection of a hundred pieces that reference and enrich each other. Your archive becomes its own moat.

Platform Independence as Defense

Here’s a vulnerability most content strategies ignore: platform dependence. If your entire reach relies on an algorithm you don’t control, you don’t have a moat. You have a lease that can be terminated.

Google changes its search algorithm. Your organic traffic disappears overnight. Social media platforms adjust their feeds. Your reach drops by seventy percent. These aren’t hypothetical scenarios. They happen regularly. Building your castle on rented land means you’re always one policy change away from irrelevance.

A real moat includes owned channels. Email lists. RSS subscribers. People who have made an active choice to hear from you directly, without an intermediary deciding whether to show them your content. This sounds old fashioned. It is old fashioned. That’s precisely why it works.

Owned channels grow slower than viral social media hits. They require more effort to build. But they’re defensive. They’re yours. When you publish something, you can reach those people directly. No algorithm required. No promotion budget required.

The strategic implication is that every piece of content should be converting some percentage of readers into owned channel subscribers. Not aggressively. Not with desperate pop ups and lead magnets. But with a simple value proposition: if you found this useful, you’ll probably want to see what else we publish.

The Economics of Attention Retention

There’s a economic principle at work in content that most strategies miss. The cost of acquiring attention is high and rising. The cost of retaining attention is low and stable.

Getting someone to notice you the first time requires you to be remarkable enough to break through the noise. You’re competing with everything else they could pay attention to. That’s expensive in effort, creativity, and often money.

Getting someone to pay attention the second time is easier. They already know you. They have context. If the first experience was good, they’re predisposed to give you attention again. The tenth time is easier still. By then it’s habit.

Most content strategies optimize for the first encounter. They chase new eyeballs. They focus on top of funnel. This makes sense if you’re bad at retention. If people try you once and leave, you have no choice but to constantly find new people.

But if you can make the content good enough that people come back, the economics shift dramatically in your favor. Your acquisition cost per meaningful relationship drops over time. Your competitors, meanwhile, are stuck in an endless loop of expensive acquisition.

The moat here is turning readers into returners. That requires earning it with every piece. It requires not publishing filler. It requires respecting attention as the scarce resource it is.

Why Boring Wins Eventually

There’s a particular kind of content moat that deserves special attention because it’s so undervalued. Comprehensive, well maintained, boring reference material.

Everyone wants to go viral. Everyone wants the hot take that spreads. Nobody wants to maintain the detailed guide that answers the same question a thousand people ask every month. But that guide, updated regularly, comprehensive in scope, is defensive gold.

When you become the place people bookmark for reference, you own that topic. You’re not in the feed competing for attention. You’re in the bookmarks, the citation lists, the links people share when someone asks a question in a forum. This is less exciting than viral content. It also compounds more reliably.

The mistake is thinking reference content doesn’t need to be good. It does. It needs to be thorough, clear, current, and trustworthy. Boring doesn’t mean lazy. It means useful in an unsexy way.

Building this kind of moat requires patience. Reference content doesn’t explode. It accumulates authority slowly. Over months and years, it becomes the definitive source. At that point, displacing it requires someone else to create something significantly better and then convince everyone who’s already linking to you to change their links. That’s a tall order.

The Long Game

Content moats aren’t built quickly. They’re built through decisions that prioritize durability over immediate results. They’re built by being willing to look inefficient in the short term to be defensible in the long term.

This requires a certain kind of organizational courage. It means telling stakeholders that you’re going to publish less frequently but with more depth. It means saying no to trendy topics that don’t fit your strategic focus. It means investing in things that won’t show ROI for quarters or years.

But the alternative is being perpetually vulnerable. Publishing on the treadmill, constantly hustling for attention, always one competitor away from losing relevance.

The castle with a moat takes longer to build than the sandcastle. But when the tide comes in, only one is still standing.