Table of Contents

Every organization that has ever suffered a major operational failure had a compliance manual. Most had entire departments dedicated to following rules. Yet the failures happened anyway. This tells us something important about the difference between doing things right on paper and doing things right in practice. This reveals why company culture, not documentation, ultimately determines whether protocols translate into actual behavior.

The puzzle is not that rules fail to prevent disasters. The puzzle is why we keep believing they will.

The Checklist Illusion

Checklists work remarkably well in aviation. A pilot running through preflight checks catches errors before they become catastrophes. This success story has inspired countless organizations to adopt the same approach. If we can just document the right procedures, train people properly, and enforce compliance, surely we can eliminate operational failures.

Except we can’t.

The difference lies in what checklists can and cannot capture. In aviation, the critical variables are largely technical and the environment is controlled. The cockpit does not change its mood. The instruments do not have personal problems. The laws of physics remain consistent.

Organizations are not cockpits. They are living systems where the most critical variables are human. A compliance program can tell someone what to do, but it cannot make them care about doing it. It can mandate a process, but it cannot manufacture the judgment needed when that process meets reality.

Consider what happens when an employee spots something wrong but the approved procedure does not cover it. The rule follower waits for guidance. The culturally engaged employee acts. One organization grinds to a halt. The other adapts and survives.

The Performance Paradox

Here is where things get interesting. Organizations that focus obsessively on compliance often perform worse than those that focus on culture, even when measuring purely objective outcomes. This seems backward until you understand what excessive rule focus actually does to human behavior.

When people work in environments where following the procedure matters more than achieving the outcome, they optimize for the wrong thing. They learn to document rather than solve. They learn to cover themselves rather than take ownership. They learn that the appearance of compliance protects them better than actual results.

This creates what we might call defensive operations. Everyone is doing exactly what they are supposed to do, at least on paper, which means when something goes wrong, no individual is at fault. The failure becomes systemic, diffuse, and nearly impossible to address because the system itself is the problem.

Company culture works differently. In a strong operational culture, people internalize not just what to do but why it matters. They understand the goal behind the rule. When the rule and the goal conflict, which they inevitably will, culturally grounded employees can make intelligent trade-offs. Rule followers cannot. They lack the framework.

The Trust Equation

Every compliance requirement sends a message: we do not trust you to make the right decision on your own. Sometimes this message is warranted. Sometimes it is catastrophic.

Organizations need rules, obviously. The question is about balance and intent. Are rules designed to empower good judgment or replace it? Are they meant to guide decisions or eliminate them?

The distinction matters because trust and surveillance operate on different logics. When you trust someone and give them autonomy within boundaries, you activate their intrinsic motivation. They feel responsible for outcomes. When you surveil someone and measure their compliance, you activate their extrinsic motivation. They feel responsible for not getting caught.

These two modes of working produce completely different operational environments. In high trust cultures, people raise problems early because they feel ownership over solutions. In low trust cultures, people hide problems as long as possible because visibility means risk.

You can guess which environment catches operational failures before they metastasize.

The Restaurant Test

Imagine two restaurants with identical menus and identical health codes. In the first, employees follow food safety rules because an inspector might show up. In the second, employees follow food safety rules because they would be horrified to make someone sick.

Both restaurants might pass inspection. Only one has genuinely safe food.

The difference is invisible to compliance metrics but obvious to anyone who works there. In the first restaurant, employees do the minimum required when someone is watching. In the second, they do what is right whether anyone is watching or not.

Scale this dynamic up to a hospital, a manufacturing plant, a financial institution. The stakes get higher but the logic remains the same. Compliance can make people go through motions. Company culture makes them give a damn.

Why Smart People Build Dumb Systems

Organizations staffed by intelligent, well-meaning people still create compliance systems that actively impede good operations. How does this happen?

The answer has to do with visibility and liability. When something goes wrong, leaders face tremendous pressure to show they are taking action. The most visible form of action is creating new rules. This demonstrates seriousness. It generates documentation. It protects against future lawsuits.

What it does not do is fix the underlying problem, which is usually cultural.

After a major operational failure, you will typically see new mandatory training, new approval layers, new reporting requirements. Everyone must now complete additional forms. Everyone must attend additional meetings. The organization becomes heavier, slower, more bureaucratic.

The actual failure often stemmed from something simpler: people knew about the problem but felt unable to speak up, or they spoke up but no one listened, or they did not care enough to notice in the first place. New forms do not fix any of these things.

This creates a vicious cycle. Compliance burdens increase. Morale decreases. People become more focused on protecting themselves than serving customers or achieving objectives. Small problems go unreported. By the time they surface, they are big problems. Leaders respond with more compliance requirements.

The Delegation Trap

Compliance programs have another subtle failing. They allow leaders to delegate culture.

A CEO can hire a Chief Compliance Officer and feel like the problem is handled. They can point to the budget, the headcount, the training completion rates. They have outsourced the responsibility for organizational behavior to a department.

Company culture does not work this way. It cannot be delegated because it emerges from the lived experience of everyone in the organization. It is how the executive team treats each other in private meetings. It is which behaviors get rewarded and which get punished. It is what happens when deadlines and values conflict.

No compliance department can manufacture these things. They emanate from leadership, whether leaders intend them to or not. An organization where executives cut corners while demanding that everyone else follow rules will develop a culture of cynicism, not compliance.

The compliance department might produce excellent documentation. The actual culture will be one where people learn that rules are for show.

What Culture Actually Means

Company culture is not free food or ping pong tables. It is the unwritten rules that govern behavior when no one is watching. It is the accumulated patterns of how an organization really works beneath what the org chart says.

In operational terms, culture is what determines whether an assembly line worker stops production when they see a defect or lets it pass to meet quota. It is what determines whether a trader reports a mistake that might lose money or tries to hide it. It is what determines whether a nurse double checks a medication or trusts that someone else already did.

These micro-decisions happen thousands of times daily in every organization. Compliance manuals cannot govern them all. Culture does.

Strong operational cultures share certain characteristics. They make visible what matters. They reward people for raising problems, not just solving them. They treat near misses as learning opportunities rather than failures. They promote people who embody desired behaviors, not just those who achieve desired results.

None of this appears in a compliance manual because it cannot be reduced to rules. It must be demonstrated, repeatedly and consistently, especially by senior leaders.

The Feedback Loop Problem

Compliance systems tend toward rigidity. Once a rule is written, it is hard to unwrite. Once a procedure is standardized, it is hard to change. The system accumulates requirements like a ship accumulates barnacles.

Company culture, when healthy, tends toward adaptation. People notice what works and what doesn’t. They share knowledge informally. They develop workarounds for stupid rules. The system evolves.

This difference becomes critical in fast-changing environments. A compliance-heavy organization responds to change by adding new rules on top of old ones. A culture-heavy organization responds to change by questioning assumptions and modifying behavior.

Consider how different companies handled the shift to remote work. Compliance-focused organizations tried to recreate office surveillance at home. They measured keyboard strokes and attendance at video calls. They created new policies about home office setups and virtual meeting etiquette.

Culture-focused organizations asked what actually mattered for getting work done and trusted people to figure out how. They focused on outcomes. They maintained connection through purpose rather than monitoring.

The first approach produced exhausted, resentful employees who performed to metrics. The second produced employees who adapted creatively to new constraints.

The Surgical Analogy

Surgery is perhaps the most rule-bound profession in existence. Protocols for everything. Checklists for every procedure. Compliance with sterilization and safety standards is not optional.

Yet great surgical teams are not merely compliant. They have cultures where everyone, regardless of rank, can speak up if they see a problem. The scrub nurse can stop the surgeon. The anesthesiologist can question the plan. This culture saves lives in ways no checklist can.

The rules provide the baseline. The culture provides the resilience. When something unexpected happens, when the patient’s anatomy is unusual, when equipment fails, the team must adapt. They need both technical protocols and the social trust to deviate from them intelligently.

Organizations that try to build safety purely through compliance end up with the protocols but not the trust. They get teams where junior members stay silent rather than challenge seniors. They get environments where unexpected situations cause paralysis because the rulebook has no answer.

The Measurement Trap

What gets measured gets managed, the saying goes. This is often true and frequently disastrous.

Compliance is easy to measure. Did the employee complete the training? Did they submit the form? Did they follow the procedure? These are yes or no questions. They generate clean data.

Culture is hard to measure. Do people feel psychologically safe raising concerns? Do teams share knowledge effectively? Do individuals take ownership beyond their job descriptions? These are matters of degree and interpretation.

The temptation is to manage what we can measure and hope it correlates with what actually matters. Sometimes it does. Often it doesn’t.

An organization can have perfect compliance scores and terrible operational performance. Everyone completes their ethics training while the company culture rewards cutting corners. Everyone submits their status reports while problems fester unreported.

The metrics show green. The reality is red.

This is not an argument against measurement. It is an argument for measuring the right things and understanding that some of the most important things resist quantification.

Building Culture Through Operations

If rules alone cannot prevent operational failures, and culture is the missing ingredient, how do organizations actually build the right culture?

The answer is disappointingly simple and frustratingly difficult: through consistent behavior over time, particularly from leaders.

Culture is not a program you launch. It is a pattern you demonstrate. Every decision about who to hire, who to promote, who to fire sends a message about what the organization truly values. Every choice about which corners can be cut and which are sacred reveals actual priorities.

When leaders say safety is paramount but reward managers who cut maintenance costs, the organization learns what really matters. When executives talk about innovation but punish failed experiments, people learn to play it safe. The stated values mean nothing. The demonstrated values mean everything.

This is why culture change is so hard. It requires leaders to examine their own behavior and modify it, consistently, even when inconvenient. It requires them to make costly choices that signal genuine commitment.

Compliance programs require none of this. They require budget and bureaucracy. They are much easier to implement, which is part of why they are so popular.

The Path Forward

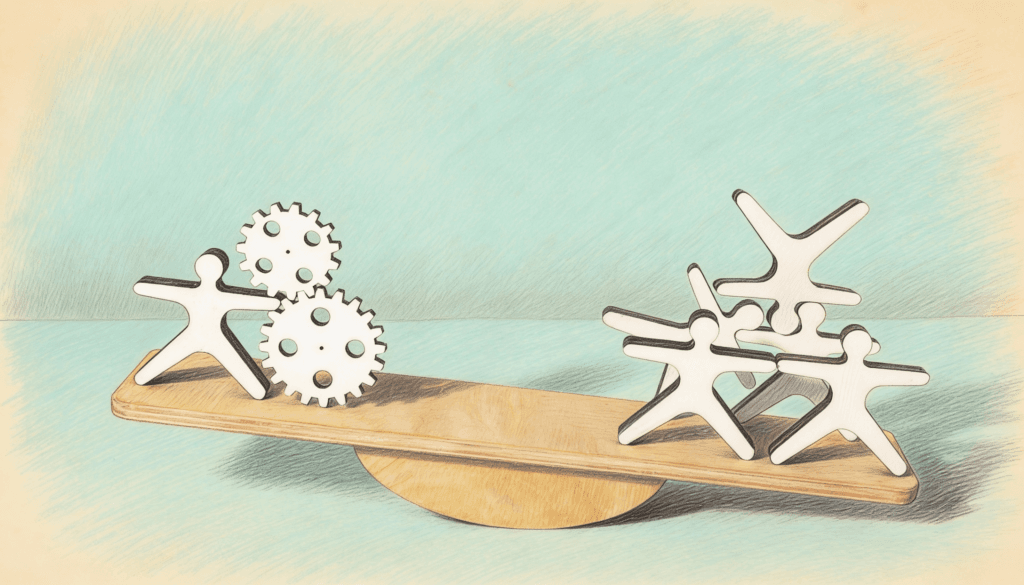

Organizations need both culture and compliance, but they need to understand what each can and cannot do. Compliance provides the floor. Culture provides the ceiling.

Rules can establish minimum standards. They can codify hard-won lessons. They can protect against known failure modes. This is valuable. It is not sufficient.

Culture determines what happens in the gray areas, which is most of operational life. It determines whether people bring their judgment to work or leave it at home. It determines whether the organization adapts or calcifies.

The practical implication is that operational excellence requires investing in things that do not fit neatly into compliance frameworks. It requires leaders who model desired behaviors. It requires systems that surface problems rather than hide them. It requires patience with the messy, slow work of building trust and shared purpose.

None of this generates the same satisfying deliverables as a compliance program. You cannot point to culture the way you point to a training module. But you can see it in outcomes. You can see it in how organizations respond when things go wrong. You can see it in whether failures are learning opportunities or blame-finding exercises.

The organizations that get this right do not choose between culture and compliance. They understand that rules without culture produce brittle systems that follow processes off cliffs. They invest in both, knowing that one enables the other.

They build compliance systems that empower judgment rather than replace it. They build cultures that take rules seriously while remaining adaptable. They recognize that operational excellence emerges not from perfect procedures but from imperfect people who care enough to do things right.