Table of Contents

Most business dashboards look like they were designed by people who believe more is more. Charts stacked on charts. Metrics breeding more metrics. Colors that would make a peacock nervous. And somewhere in all that visual noise, the actual story your business is trying to tell gets lost.

The irony is thick. We create scorecards to see our business more clearly, then drown them in so much data that we need another scorecard just to understand the first one.

This isn’t really about your inability to wrangle Excel into submission or your distance from a computer science degree. It’s about something more fundamental. Most people treat business visualization like translation, moving numbers from one place to another. But visualization is actually interpretation. It’s deciding what matters and what that meaning looks like.

The Spreadsheet Trap Nobody Talks About

Spreadsheets are magnificent tools. They’re also traps disguised as solutions.

When you build your scorecard in a spreadsheet, you’re not just organizing data. You’re inheriting a specific worldview about how information should behave. Rows and columns. Cells and formulas. Everything discrete, everything separated, everything atomized into its smallest possible unit.

But businesses don’t actually work that way. They’re networks of cause and effect, feedback loops, cascading consequences. When revenue drops, is it marketing? Sales? Product quality? Customer service? The honest answer is usually “yes, somehow, all of them.” But the spreadsheet forces you to pick a cell.

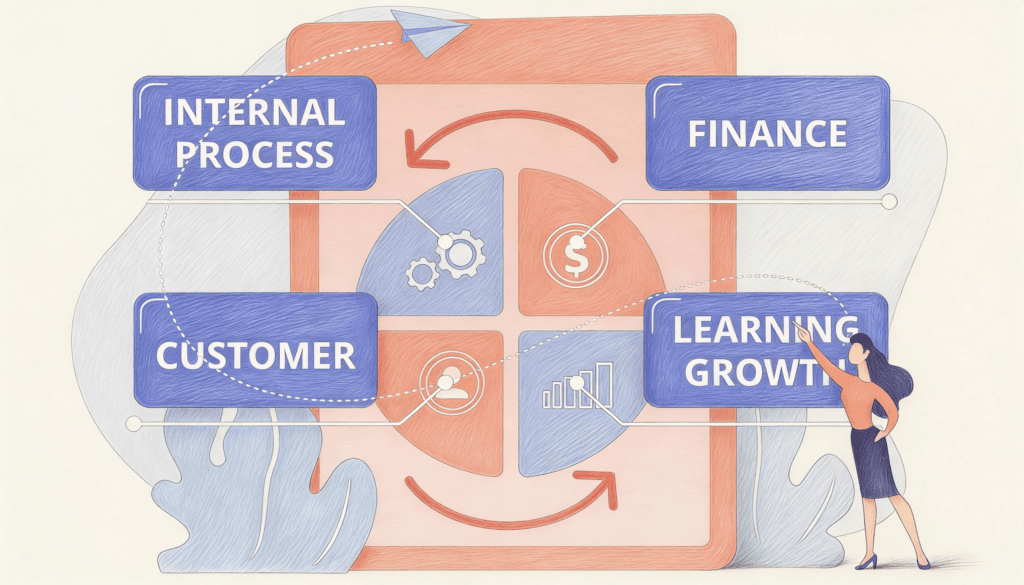

This is why so many scorecards end up as what one executive I know calls “dashboard vomit.” Every department demands their metrics get included. Finance wants their numbers. Marketing wants theirs. Operations needs representation. The scorecard becomes a political document where visibility equals importance, and suddenly you’re tracking forty metrics when you really only need to watch five.

The solution isn’t better spreadsheet skills. It’s recognizing that the medium is shaping the message in ways you never agreed to.

What Visualization Actually Does

Here’s the thing about human brains: we’re pattern recognition machines wearing business casual.

You can stare at a column of numbers for ten minutes and miss the trend that becomes obvious the moment someone draws a line through those same points. This isn’t a bug in how we’re built. It’s a feature. We evolved to spot the rustle in the grass that might be a predator, not to compare Q3 variance against forecast.

Visualization doesn’t just make data prettier. It makes it thinkable.

When you see a dashboard where customer acquisition cost and customer lifetime value are plotted together, your brain does something spreadsheets can’t. It grasps the relationship. Not just intellectually, but almost physically. You can see when the lines are healthy distances apart. You can feel when they’re converging in ways that spell trouble.

This is why the best business visualizations often look simple to the point of boring. They’re not trying to impress you with their complexity. They’re trying to hand your brain exactly what it needs to understand what’s happening.

Think about how pilots use instruments. A pilot doesn’t want artistic creativity in their altimeter. They want instant clarity about whether they’re flying level or about to become a cautionary tale. Business scorecards should aspire to this same ruthless clarity.

The Map Is Not the Territory, But It Still Matters

There’s a famous idea in philosophy that the map is not the territory. A representation of reality isn’t the same as reality itself. True enough. But here’s what gets missed: bad maps get you more lost than no maps at all.

A bad business scorecard doesn’t just fail to help. It actively misleads. It tells you stories about your business that aren’t true. It makes you confident about things you should be uncertain about. It hides problems in plain sight by showing you everything except what matters.

The classic example is focusing on vanity metrics. Website traffic goes up, and everyone celebrates. But if none of those visitors buy anything, you’ve just gotten very good at attracting window shoppers. The number went up. The visualization showed green. The business didn’t actually improve.

This is where most scorecard projects die. Not from lack of technical skill, but from lack of clarity about what they’re actually trying to show. People build elaborate visualizations of the wrong things, then wonder why their decisions don’t get better.

Starting With the Question, Not the Data

Every good visualization begins with a question.

Not “what data do we have?” but “what do we need to know?” The difference seems subtle. It’s actually everything.

When you start with the data, you build a museum. Look at all these interesting numbers we collected! When you start with the question, you build a compass. Here’s the direction we need to go, and here’s whether we’re heading there.

Let’s say your question is: “Are we building a sustainable business or just buying growth that will collapse the moment we stop spending?” That’s a real question with real consequences. Now suddenly you know what you need to visualize.

- The relationship between organic and paid growth.

- Customer retention curves.

- Unit economics over time.

Notice how different this is from “let’s visualize all our marketing data.” The first approach gives you five focused charts that tell a story. The second gives you thirty scattered metrics that require a decoder ring.

The best business leaders I’ve encountered do this instinctively. They don’t ask to see all the data. They ask specific questions, and they want visualizations that answer those questions without making them work for it.

The Power of Subtraction

There’s a study about composers that stuck with me. When shown a piece of music, amateurs add notes to improve it. Professionals remove notes. They know that clarity comes from what you leave out, not what you cram in.

Scorecards work the same way.

Your instinct when building a visualization is to include everything that might possibly matter. Better to have it and not need it, right? But this is exactly backward. Every element you add is another thing your brain has to process before it gets to meaning. You’re not creating completeness. You’re creating friction.

The hardest part of building a good scorecard isn’t learning the visualization tools. It’s getting comfortable with exclusion. Deciding that these three metrics matter and these seventeen don’t. That takes more courage than technical skill.

Here’s a useful exercise: build your ideal scorecard, then force yourself to remove half of it. Not the least important half. Actually half. This violent constraint forces clarity. You can’t hide behind “well, someone might need this.” You have to make choices about what’s actually essential.

More often than not, the scorecard you’re left with is more useful than what you started with. Not because you removed the wrong things, but because you forced yourself to understand what the right things actually are.

The Choreography of Time

Most scorecards treat time like a dimension you glance at and move on. But time is where the story lives.

A single number tells you almost nothing. Revenue is ten million dollars. Okay. Compared to what? Compared to when? Is that going up or down? Fast or slow? According to plan or wildly off track?

The best visualizations don’t just show you where you are. They show you how you got here and where the momentum is taking you. This is why trend lines matter more than points.

Think about a doctor reading your vital signs. Your blood pressure at this exact moment is useful information. But your blood pressure compared to last month, and the month before, and whether it’s trending up or down tells a story about your health that a single reading never could.

Business scorecards need this same temporal awareness. You’re not trying to capture a moment. You’re trying to understand a process. And processes only make sense when you watch them unfold.

When Simple Becomes Simplistic

There’s a point where simplification becomes oversimplification, and you need to know where it is.

A single number that combines too many things stops being useful. If you average together metrics that move for different reasons, you get a number that moves for no particular reason at all. It’s like mixing all the paint colors together and calling the resulting mud “a complete palette.”

This is the dark side of executive dashboards. The desire to summarize everything into a handful of numbers that senior leaders can glance at. Sometimes it works. Often it just hides the actual dynamics of the business under a layer of false simplicity.

The solution isn’t to abandon simplification. It’s to be thoughtful about what you combine and what you keep separate. Some things naturally go together. Customer acquisition cost and customer lifetime value are two sides of the same equation. But revenue and employee satisfaction? Those are different stories that happen to occur in the same business. Mashing them together doesn’t create insight.

Tools Don’t Think For You

Let’s address the elephant in the room. There are dozens of tools that promise to turn you into a visualization wizard without any of the wizard training. Plug in your data, pick a template, presto.

These tools are useful. They’re also not magic.

They can make it easier to create charts. They can’t make you understand which charts matter. They can apply color schemes that look professional. They can’t tell you what story your data is actually telling. They can automate the creation of dashboards. They can’t do the thinking about what should be on them.

The tool you choose matters less than people think. Whether you use Tableau, Power BI, HubSpot or some newer shinier option, you’re still making the same fundamental decisions. What to measure. How to display it. What to emphasize. What to ignore.

People often get stuck in tool selection because it feels like progress. It’s easier to debate the features of different platforms than to have the harder conversation about what you’re actually trying to understand about your business.

Pick something that works and move on. The visualization quality depends far more on the quality of your thinking than the sophistication of your software.

The Human Element Nobody Plans For

Here’s what happens with most scorecard projects. Someone builds something thoughtful. It gets rolled out. People look at it for a week. Then they go back to whatever they were doing before.

This isn’t because the scorecard was bad. It’s because changing how people see information requires changing how they think about their work, and that’s a cultural project disguised as a technical one. The best visualizations become part of how teams talk to each other. They create a shared language.

When someone says “the gap is widening” everyone knows exactly which chart they mean and what that implies about the business. The scorecard isn’t just information. It’s infrastructure for conversation.

This means thinking about your audience from the start. Who’s going to look at this? How often? In what context? A scorecard that works in a Monday morning leadership meeting might completely fail as something individuals check throughout the week. Different purposes need different designs.

Making It Stick

The final piece is making your scorecard something people actually use rather than something that gets glanced at and forgotten.

This means building rituals around it. Regular meetings where specific metrics get discussed. Clear ownership of what happens when numbers move in unexpected directions. Consequences, good and bad, that flow from what the scorecard reveals.

Without this, even the most beautiful visualization is just art on the wall. Interesting to look at. Easy to ignore.

The scorecard needs to earn its place in how the business operates. It does this by being genuinely useful, consistently relevant, and ruthlessly clear about what matters. When it achieves that, people stop seeing it as another report they have to check and start seeing it as essential information they can’t work without.

That’s when you know you’ve built something that works. Not because it looks impressive, but because people would notice if it disappeared.