Table of Contents

The casino knows something most businesses forget. They don’t celebrate every person who walks through their doors. They celebrate the ones who sit down at the tables.

This distinction matters more than most marketing departments want to admit. We’ve spent decades worshipping at the altar of traffic, treating user acquisition like a numbers game where the house always wins if you just get enough people through the door. But the house doesn’t always win. Sometimes the house goes bankrupt throwing money at crowds that were never going to stay.

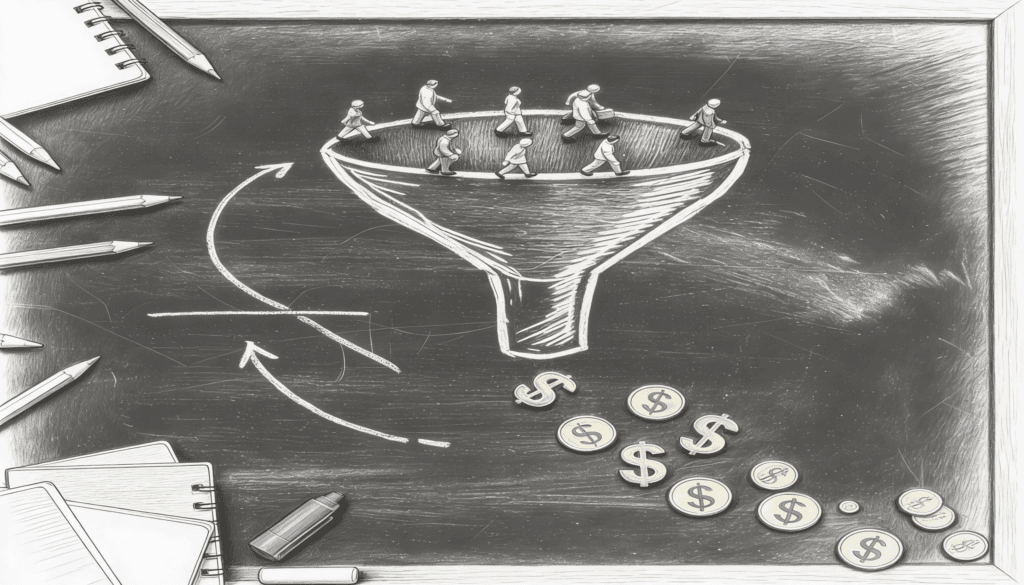

The funnel, that sacred diagram we all pretend to understand in meetings, has become less of an analytical tool and more of a wish list. We pour users in at the top and pray something valuable drips out at the bottom. This is not strategy. This is expensive hope.

The Attention Economy’s Cruel Math

Consider what happens when you acquire a million tourists. Not customers, not users, but tourists. People who showed up because your ad was pretty or your headline was provocative or because they were bored on a Tuesday afternoon. These visitors cost money to acquire. They cost money to serve. They consume bandwidth, crash servers during traffic spikes, and fill your analytics dashboard with meaningless vanity metrics that make executives feel productive.

Then they leave. Most of them within seconds. They were never going to buy anything. They were never going to return. They barely remember you exist.

But here’s what really hurts: those million tourists didn’t just cost you their acquisition price. They cost you focus. While your team optimized for their fleeting attention, the thousand people who actually wanted what you offered got a diluted experience. Your customer service team spent time on questions from people who were never going to convert. Your product team made compromises to appeal to a broader audience that wasn’t actually your audience at all.

You optimized for the wrong people, and the right people noticed.

Quality as a Strategic Moat

The companies that win long term aren’t the ones with the biggest audiences. They’re the ones with the most engaged ones. This sounds obvious until you look at how most businesses actually allocate resources. Marketing budgets skew heavily toward acquisition. Product development chases features that might attract new users rather than delight existing ones. Customer success teams measure themselves by ticket volume rather than relationship depth.

This is backwards. A thousand users who genuinely need what you offer, who integrate your product into their daily workflow, who become advocates without being asked, these people are worth more than a million who barely know you exist. Not because of some fuzzy feeling about community, but because of cold economic reality.

Quality users have higher lifetime value. They convert at higher rates. They churn less. They cost less to support because they’ve invested time in understanding your product. They provide better feedback because they actually use what you build. They refer people like themselves, which means your acquisition costs drop while your conversion rates rise.

This creates a compounding effect that volume-focused strategies can never match. Every quality user makes your business slightly better at serving quality users. Every tourist just makes you better at attracting tourists.

The Funnel Isn’t Broken, Your Inputs Are

Most funnel analysis starts at the wrong place. We measure conversion rates from visitor to signup, signup to activation, activation to purchase. We optimize each step, celebrate incremental improvements, and wonder why revenue still disappoints.

The problem isn’t in the funnel. It’s in who you’re letting into the funnel.

Imagine a restaurant that judged its success by how many people walked past its door. Then imagine that restaurant spending millions on billboards to get more people to walk past. Eventually, someone asks the obvious question: how many of these people are actually hungry for what we serve?

This is where qualification matters more than volume. The best funnels aren’t wide at the top. They’re selective. They filter aggressively for intent, for fit, for genuine need. Yes, this means smaller numbers in your top of funnel metrics. Yes, this makes your CMO nervous when presenting to the board. But it also means that everyone who enters your funnel is actually worth nurturing.

Think of it like panning for gold. You can process tons of river sediment and find flecks of gold, or you can study the geology and dig where gold actually concentrates. Both approaches find gold. One approach bankrupts you in the process.

The Permission Economy

Seth Godin talked about permission marketing decades ago, but most companies still haven’t internalized the lesson. People don’t want to be interrupted. They don’t want to be convinced. They want to be understood and served.

Quality users give you permission to be in their lives. Not because you tricked them with a clever ad or caught them at a weak moment, but because you genuinely solve a problem they have. This permission is valuable. It’s the foundation of every sustainable business relationship.

Tourists never give permission. They tolerate you briefly, then leave. You can’t build anything on tolerance.

The shift from chasing tourists to cultivating quality users requires a fundamental change in how you think about growth. Instead of asking “how do we get more people to see this,” you ask “how do we find the people who will actually value this.” Instead of broadcasting, you narrow cast. Instead of optimizing for clicks, you optimize for comprehension.

This feels risky. It feels small. It feels like leaving opportunity on the table. But opportunity is only opportunity if you can actually capture it.

When More Actually Means Less

Here’s the part that keeps founders up at night: sometimes growth makes your business worse. Not just unsustainable growth or unprofitable growth, but growth itself.

Every community has a carrying capacity. Add too many people too fast, and the culture that made the community valuable in the first place dilutes. The early adopters who championed your product feel less special, less heard. The feedback loops that helped you build something great get noisier. The signal to noise ratio in your data degrades.

Reddit understood this intuitively with subreddits. Facebook learned it the hard way with their news feed. Twitter might still be learning it. Communities stay healthy by maintaining quality thresholds, not by maximizing member counts.

Your business is a community, whether you think of it that way or not. Your users interact with your product, with your team, and often with each other. Flooding that community with tourists doesn’t make it better. It makes it louder, messier, and less valuable to the people who actually matter.

The Infrastructure Trap

Large numbers create their own problems. Server costs scale linearly, but the complexity of serving diverse audiences scales exponentially. When you have a million tourists, you need infrastructure to handle peak loads, even though most of those peaks represent people who will never pay you a dollar. You need broader customer support capacity. You need more generic product features that serve the mythical average user who doesn’t actually exist.

Meanwhile, the thousand quality users suffer. Response times slow during tourist surges. Features get bloated with options they’ll never use. The product becomes harder to understand because it’s trying to be everything to everyone.

Measuring What Matters

The metrics that dominate startup culture are mostly initial. Monthly active users, total downloads, pageviews, these numbers tell you almost nothing about business health. They’re vanity metrics wearing business casual.

Quality users show up in different metrics. Retention curves that flatten rather than declining. Support costs per customer that drop over time as users become experts. Net Promoter Scores that rise without prompting. Feature adoption rates among power users. Revenue per employee as your team becomes more efficient at serving a coherent audience.

These metrics are harder to manipulate. You can buy tourists, but you can’t buy genuine engagement. You can trick people into signing up, but you can’t trick them into staying. The measurements that reflect quality are the measurements that resist gaming.

This creates a useful forcing function. When you commit to quality metrics, you commit to actually building something worth using. You can’t fake your way to strong retention or high engagement. You have to do the work.

The Compounding Advantage

Here’s where the math gets interesting. Tourists have negative compounding effects. Each one slightly degrades your infrastructure, your focus, and your culture. They create drag. Quality users have positive compounding effects. Each one teaches you something about your best customers. Each one provides use cases that help you build better features. Each one potentially brings others like them.

This compounding accelerates over time. A business built on quality users gets exponentially better at serving quality users. A business built on tourist volume gets linearly better at processing tourists, but never actually improves its core value proposition.

The companies that dominate their categories long term almost always took the quality path. They started with intense focus on a small group of users who really needed what they offered. They resisted the temptation to chase every possible customer. They built deep moats through excellence rather than wide moats through mediocrity.

Stripe could have built a payment processor for everyone. Instead, they built one for developers. That specificity made them better for developers than anyone else, which eventually made them better for everyone. But they got there by starting narrow and going deep.

The Courage to Say No

The hardest part of focusing on quality users is turning away volume. Every tourist represents potential revenue, however unlikely. Every viral moment represents potential growth, however unsustainable. Saying no to these opportunities feels like leaving money on the table.

But money on the table isn’t money in your bank account. And attention that can’t convert isn’t really attention at all. It’s distraction dressed up as opportunity.

The best product leaders develop a talent for saying no. No to features that would attract tourists but confuse core users. No to marketing channels that drive volume but not value. No to partnerships that would dilute the brand. This selectivity feels constraining, but it’s actually liberating. When you know who you serve and why, every decision becomes simpler.

Basecamp built an entire business philosophy around this. They explicitly limit their product’s features and their company’s size. They turn away customers who want things they don’t offer. This seems insane by conventional Silicon Valley logic, where growth at all costs dominates strategic thinking. But Basecamp is profitable, sustainable, and beloved by its users precisely because it serves those users obsessively rather than chasing every possible market.

Finding Your Thousand

If quality beats volume, the obvious question becomes: how do you find quality users without first processing massive volume?

The answer lies in understanding that quality users are searching for you just as actively as you’re searching for them. They have a problem. They need a solution. They’re motivated. Your job isn’t to convince them they have a problem or create desire where none exists. Your job is to be findable and understandable when they come looking.

This changes everything about go to market strategy. Instead of interruptive advertising, you focus on being present in the places your ideal users already look for solutions. Instead of broad messaging, you speak specifically to the exact problem you solve. Instead of trying to appeal to everyone, you risk alienating some people to resonate deeply with the right ones.

The specificity feels dangerous. What if you’re too narrow? What if you exclude potential customers? But specificity is what makes you memorable. Generic appeals get ignored. Specific ones get shared by the people who recognize themselves in your message.

The Long Game

Building for quality over volume requires patience. The growth curves look different. Slower initial adoption, but better retention. Lower top line numbers, but stronger unit economics. Less impressive presentations to investors, but more sustainable businesses.

This patience is increasingly rare. Public markets reward growth. Venture capital rewards growth. Media coverage rewards growth. The entire ecosystem pushes toward prioritizing volume even when volume destroys value.

But the companies that actually last, that build something durable rather than something impressive, almost always choose quality over volume eventually. The question is whether they make that choice strategically from the beginning or desperately after chasing volume nearly kills them.

The funnel analysis that matters isn’t about conversion rates at each stage. It’s about whether the people entering your funnel are the people you built your product for. Get that right, and everything else gets easier. Get that wrong, and nothing else matters.

Your thousand quality users are out there, looking for exactly what you offer. The question is whether you’ll have the discipline to serve them exceptionally rather than serving a million tourists adequately. One path builds a business. The other builds a traffic report.