Table of Contents

When Gordon Ramsay walks into a struggling restaurant on Kitchen Nightmares, he doesn’t immediately redesign the menu or retrain the staff. He opens the walk-in refrigerator. And what he finds there tells him everything he needs to know.

Rotting lettuce pushed behind fresh produce. Frozen fish labeled as fresh. Ingredients purchased months ago sitting next to tonight’s specials. The kitchen might have state of the art equipment and a chef with impressive credentials, but none of that matters when the foundation is rotten.

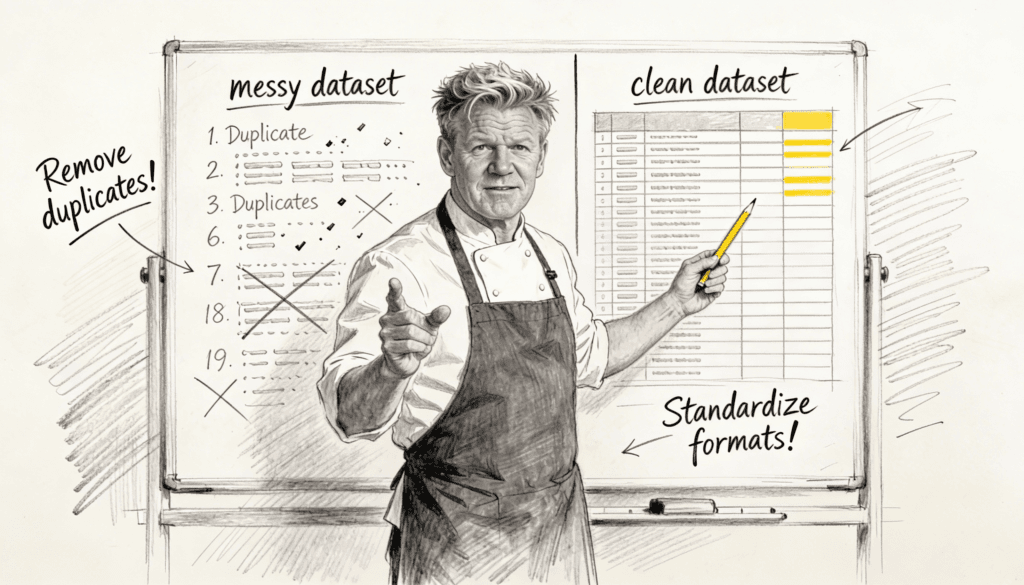

Data preparation is your walk-in refrigerator. It’s the unglamorous work that happens before the cooking starts, before the presentation, before the critics arrive. And just like in a restaurant kitchen, no amount of skill in the later stages can compensate for spoiled ingredients at the start.

The Mise en Place Principle

Professional chefs live by mise en place, a French term meaning everything in its place. Before service begins, every ingredient is prepped, measured, and organized. Onions are diced. Sauces are portioned. Garnishes are ready. This isn’t busywork or obsessive organization for its own sake. It’s the difference between a kitchen that flows and one that drowns during the dinner rush.

Ramsay is fanatical about this preparation because he understands something fundamental: cooking is a time-sensitive performance. When orders start flying in, there’s no opportunity to stop and figure out where things are or realize you forgot to defrost something. The quality of your preparation directly determines the quality of your output under pressure.

The same logic applies to data work. When stakeholders need insights, when decisions are waiting, when the business is moving, you can’t suddenly discover that your data sources don’t align or that half your records are duplicates. The analysis phase is performance time. The preparation phase is when you earn the right to perform well.

Yet most organizations approach data preparation the way amateur cooks approach mise en place. They know it’s probably important, but they’re impatient to get to the exciting part. They want to skip straight to the insights, the visualizations, the strategic recommendations. They treat data preparation as an unfortunate prerequisite rather than the foundation of everything that follows.

Fresh Ingredients Matter More Than Complex Recipes

One of Ramsay’s most consistent critiques is restaurants trying to do too much with too little. He finds menus with seventy items and a kitchen that can’t properly execute seven. The ambition is admirable. The execution is impossible.

When he simplifies these menus, he’s not dumbing anything down. He’s acknowledging a truth that applies far beyond restaurants: complexity built on a weak foundation collapses. A simple dish made with fresh, quality ingredients will always outperform an elaborate dish made with freezer-burned components and wilted vegetables.

In data work, we see this pattern constantly. Organizations invest in advanced analytics, machine learning models, and sophisticated visualization tools while their underlying data is a mess. They’re trying to make a soufflé with expired eggs.

The technology industry loves to sell complexity. Every vendor promises that their platform will unlock insights you never knew existed. And perhaps it could, if you fed it data that was clean, consistent, and reliable. But when you feed messy data into sophisticated systems, you don’t get sophisticated insights. You get sophisticated garbage.

This creates a strange irony. The organizations most excited about cutting edge analytics are often the ones least prepared to use it effectively. They’ve skipped the boring work of standardizing field names, reconciling data sources, and establishing consistent definitions. They want the Michelin star before they’ve learned to properly wash their vegetables.

The Taste Test Mentality

Ramsay tastes everything. Not just at the end, but throughout the cooking process. He tastes the sauce before it goes on the plate. He tastes it again after. This isn’t perfectionism or showmanship. It’s quality control baked into the process itself.

Most data preparation happens in darkness. Someone cleans the data, transforms it, loads it into a system, and hopes for the best. The first time anyone really examines whether the preparation was done correctly is when the analysis produces weird results or when a dashboard shows numbers that don’t make sense.

By then, you’re not just dealing with bad data. You’re dealing with decisions made on bad data, reports distributed based on bad data, and a loss of confidence that’s hard to rebuild. The restaurant equivalent would be serving dishes to customers and only discovering the fish was spoiled when they start complaining.

Building validation into your preparation process means checking your work at every stage. When you merge two datasets, you verify the match rates. When you transform a field, you spot check the results. When you apply business rules, you confirm they’re working as intended. This feels like it slows you down. And it does, slightly, in the moment. But it saves you from the much larger slowdown of having to redo everything later or, worse, building an entire analysis on a flawed foundation.

The compounding nature of data errors makes this especially critical. A small mistake in preparation doesn’t stay small. It gets built upon, referenced, and incorporated into downstream processes. That mislabeled ingredient doesn’t just ruin one dish. It ruins every dish that uses it, and you might not discover the problem until you’ve served dozens of plates.

When Fresh Isn’t Fresh

One of Ramsay’s recurring frustrations is restaurants lying about their ingredients. They claim everything is fresh when much of it comes from a freezer or a can. The menu says homemade but the pasta came from a supplier. They’re not just deceiving customers. They’re deceiving themselves about what they’re capable of delivering.

Data preparation forces a similar reckoning with reality. Organizations often believe their data is better than it actually is. They have systems that have been running for years, reports that get generated automatically, and processes that feel established. The assumption is that if data is flowing, it must be flowing correctly.

This assumption is dangerous. Long-running systems accumulate technical debt. Business rules that made sense five years ago may no longer apply. Fields that were once mandatory become optional. New data sources get added without proper integration. The data pipeline that once worked well becomes a patchwork of workarounds and exceptions.

Admitting this requires honesty that many organizations resist. It means acknowledging that the dashboard everyone relies on might be built on shaky ground. It means accepting that quick fixes have accumulated into structural problems. It means recognizing that the data quality issues people have been working around are symptoms of deeper preparation failures.

But this honesty is liberating. Once you stop pretending your ingredients are fresh, you can actually make them fresh. Once you acknowledge the preparation problems, you can fix them. The alternative is continuing to serve dishes you know aren’t quite right while hoping nobody notices.

The Danger of Too Many Cooks

Ramsay often finds kitchens where everyone is working but nobody is responsible. Orders get confused. Dishes sit under heat lamps. Timing falls apart. There are plenty of people cooking, but there’s no coordination, no clear ownership, no system.

Data preparation in large organizations often mirrors this dysfunction. The sales team maintains their customer database. Marketing has their own version of customer data. Finance has yet another. IT manages the data warehouse. Analytics tries to make sense of it all. Everyone is doing data work, but nobody owns the end-to-end preparation process.

This fractured ownership creates endless problems. The same customer exists in three systems with three different spellings of their company name. Date formats differ across platforms. What counts as a completed sale means something different to each department. Everyone is preparing data, but they’re preparing it for their own purposes, using their own standards, following their own logic.

The solution isn’t necessarily to centralize everything under one team. It’s to establish clear responsibilities and consistent standards. Somebody needs to own the definitions. Somebody needs to ensure data quality. Somebody needs to be accountable when preparation fails. Without this ownership, you end up with the data equivalent of a kitchen where everyone is cooking but nobody is coordinating.

Why Bad Data Preparation Persists

If data preparation is so important, why do organizations consistently underinvest in it? The answer is the same reason restaurants let their walk-in refrigerators become disaster zones. It’s not exciting. It’s not visible to customers. It doesn’t feel strategic.

When Ramsay walks into a restaurant, the owners want to talk about their concept, their vision, their unique approach to cuisine. They don’t want to talk about inventory management or food storage protocols. Those things feel beneath the level of creative and strategic thinking they want to be operating at.

Similarly, business leaders want to talk about artificial intelligence, predictive analytics, and data-driven transformation. They don’t want to hear about data quality issues, schema inconsistencies, or the need to standardize field definitions. That work feels technical rather than strategic, operational rather than transformational.

This creates a trap. The unglamorous preparation work gets delayed or underfunded because it doesn’t generate immediate excitement. But without that foundation, the exciting initiatives fail. The machine learning model produces unreliable predictions because it was trained on inconsistent data. The real-time dashboard shows misleading trends because the underlying data streams aren’t properly aligned. The strategic insights are wrong because the preparation was sloppy.

The irony is that good preparation makes everything else easier. When your data is clean, consistent, and well organized, analysis becomes faster. Insights become more reliable. New projects launch more quickly because you’re not starting from scratch each time. Good preparation is the ultimate strategic investment, even though it feels tactical in the moment.

The Preparation Mindset

What Ramsay brings to struggling kitchens isn’t just culinary skill. It’s a mindset that elevates preparation from a chore to a craft. He doesn’t tolerate the attitude that preparation is just something you rush through to get to the real work. In his view, preparation is the real work.

This mindset shift is what data teams and organizations need. Data preparation isn’t the boring stuff you do before the analysis. It’s not the technical detail you delegate to junior team members. It’s not the phase you skip when you’re in a hurry. It’s the foundation that determines whether everything else succeeds or fails.

Adopting this mindset means changing how you talk about data preparation. Instead of treating it as overhead, recognize it as value creation. Instead of measuring your team by how quickly they produce analyses, measure them by how reliable those analyses are. Instead of celebrating the sophisticated model, celebrate the clean data that made it possible.

It also means changing how you allocate resources. If data preparation typically consumes sixty or seventy percent of the time in analytics projects, that’s not a problem to solve. It’s a reality to embrace and support. Trying to shortcut that time by rushing preparation or skipping validation steps is like trying to speed up cooking by skipping the defrosting process. You can do it, but the results will be worse.

Building the System

Individual behavior matters, but systems matter more. Ramsay doesn’t just tell restaurant staff to be more careful. He redesigns their systems. He simplifies menus so preparation is manageable. He reorganizes storage so fresh ingredients are easy to access and old inventory is easy to spot. He creates processes that make good preparation the default rather than something that requires exceptional effort.

The same principle applies to data preparation. You can’t rely on individuals to manually verify every data point or catch every inconsistency. You need systems that make good preparation easier than bad preparation.

This means automation where appropriate. Automated data quality checks that run every time data is loaded. Standardized transformation scripts that everyone uses rather than each person writing their own. Clear documentation that explains what each field means and how it should be used. Version control so you can track changes and roll back mistakes.

But automation isn’t enough. You also need cultural systems. Regular reviews where teams examine data quality metrics. Clear escalation paths when preparation problems are discovered. Incentives that reward thorough preparation rather than just speed of delivery. A culture where admitting a data quality issue is seen as responsible rather than embarrassing.

These systems don’t emerge naturally. They require intentional design and ongoing maintenance. They require leadership that understands preparation isn’t just a technical concern but a strategic capability. They require patience to build something sustainable rather than just patching problems as they arise.

The Payoff Nobody Sees

The frustrating truth about excellent preparation is that when it’s done well, it’s invisible. Diners don’t praise a restaurant because the walk-in refrigerator is organized. They praise it because the food is delicious. They don’t realize the delicious food was only possible because of that organized refrigerator.

Similarly, when data preparation is done well, nobody notices it. Stakeholders see the insights. They appreciate the quick turnaround. They trust the analysis. They don’t see the hours spent cleaning data, reconciling sources, and validating transformations. They don’t realize those insights were only possible because of that invisible preparation work.

This creates a recognition problem. The people doing excellent preparation work often don’t get credit for it. The glory goes to the final analysis, the strategic recommendation, the impressive visualization. The preparation work that made it all possible remains in the background.

Addressing this requires intentional effort to make the invisible visible. Share metrics on data quality improvements. Highlight how thorough preparation enabled faster analysis. Celebrate the team member who caught a data inconsistency before it caused problems. Create space to acknowledge that the analysis everyone loved was built on a foundation of careful preparation.

Gordon Ramsay’s genius isn’t his ability to cook. Plenty of chefs can cook at a high level. His genius is understanding and communicating that great cooking starts long before you turn on the stove. It starts with how you source ingredients, how you store them, how you prepare them, how you organize your station.

Great data work starts long before you build your first visualization or run your first model. It starts with how you collect data, how you store it, how you clean it, how you prepare it for use. Master that foundation, and everything else becomes possible. Skip it, and nothing else really matters. The walk-in refrigerator tells the whole story. You just have to be willing to look inside.