Table of Contents

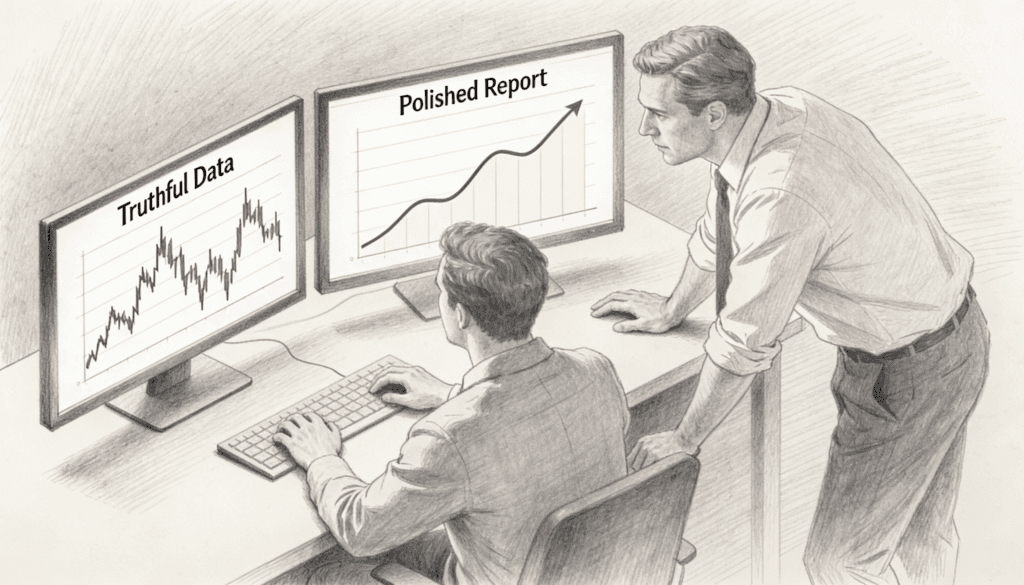

The spreadsheet looks perfect. Every assumption documented, every variable accounted for, sensitivities mapped across three scenarios: base, upside, downside. The presentation flows like water. Your boss nods approvingly.

And yet, somewhere in your gut, you know you’ve just spent two weeks building an elaborate monument to what everyone already wanted to hear.

This is the dirty secret of scenario analysis. We treat it as a rigorous discipline, a scientific approach to navigating uncertainty. We invoke it in strategy meetings with the gravity of monks discussing scripture. But strip away the formatting and the carefully chosen axis labels, and you’ll often find something closer to organizational theater than genuine preparation for the future.

The Comfort of the Expected

There’s a reason most scenario planning exercises produce three futures that look suspiciously like “things get a bit better,” “things stay roughly the same,” and “things get a bit worse, but not catastrophically so.” These scenarios don’t emerge from the data. They emerge from what feels acceptable to present in a conference room.

Think about it. When did you last see a scenario planning deck that included “our entire business model becomes obsolete within eighteen months”? Or “our largest competitor decides to give away their core product for free”? These aren’t wild fantasies. Both have happened repeatedly across industries. Blockbuster had plenty of smart people running scenarios. So did Nokia. So did every newspaper that watched Craigslist vaporize their classified ad revenue.

The scenarios they didn’t run were the ones that mattered.

This isn’t about intelligence or effort. It’s about incentives. Your boss has his own boss. That boss has a board. The board has analysts watching quarterly earnings. Everyone in this chain needs to believe that the future is manageable, that risk is quantifiable, that with proper planning we can navigate whatever comes next. Scenario analysis becomes the vehicle for this collective reassurance rather than a genuine tool for confronting uncertainty.

The Map That Validates the Territory

Real scenario planning should make you uncomfortable. It should force conversations nobody wants to have. It should identify dependencies that, once illuminated, reveal how fragile your current strategy actually is.

Instead, we often work backwards. We start with the strategy we’ve already committed to, then construct scenarios that validate it. The base case assumes our strategy works. The upside case assumes it works better than expected. The downside case assumes some temporary headwinds that we’ll weather because, well, we’re resilient and adaptable and other things that sound good in mission statements.

This is like a ship’s captain commissioning maps that only show calm seas and favorable winds. Technically, those conditions do exist. They’re even common. But they’re not what determines whether you sink or sail.

The problem compounds when scenario analysis becomes a checkbox in the corporate governance process. Do we have scenarios? Yes. Are they documented? Yes. Did we review them quarterly? Yes. Excellent, we’re being responsible stewards. Never mind that all three scenarios assume our key suppliers remain stable, our regulatory environment stays predictable, and consumer preferences shift only along dimensions we’re already tracking.

What Gets Measured Gets Massaged

Here’s where the quant people will object. They’ll point to their Monte Carlo simulations, their decision trees, their carefully calibrated probability distributions. Look at all this rigor, they’ll say. These aren’t just stories. These are models.

And they’re right, up to a point. The math is real. The techniques are sophisticated. But math is a tool for processing inputs, not for determining which inputs matter. Garbage in, gospel out.

The most dangerous scenarios are the ones that don’t fit cleanly into your model. Maybe they involve variables you don’t know how to quantify. Maybe they require assumptions that sound absurd when spoken aloud in a meeting. Maybe they implicate political realities within the organization that nobody wants to acknowledge.

So those scenarios get smoothed away. Not through conspiracy, but through the gentle pressure of wanting to seem reasonable, credible, professional. The model becomes a sophisticated mechanism for excluding inconvenient possibilities.

Consider how companies modeled pandemic risk before 2020. Most had some version of it in their enterprise risk frameworks. But the scenarios they ran generally assumed a health crisis would be regional and contained, not a multi year global disruption of basically everything. Why? Because modeling the latter felt like cosplaying disaster. It seemed disproportionate. Alarmist. Not the kind of thing serious business people spend time on.

Then reality arrived, indifferent to what seemed proportionate.

The Stakeholder Problem

Part of what makes honest scenario analysis so hard is that different stakeholders need different things from it, and those needs conflict.

Executives need scenarios that help them make decisions without paralyzing the organization. Investors need scenarios that demonstrate management is thinking ahead without suggesting the ship is rudderless. Regulators need scenarios that show you’re managing risk without admitting to vulnerabilities that might trigger intervention. Employees need scenarios that acknowledge uncertainty without creating panic.

Try building a scenario framework that serves all those masters simultaneously. You’ll end up with something carefully calibrated to offend no one and genuinely prepare for nothing.

The hidden cost is strategic clarity. When your scenarios are designed to be politically acceptable rather than strategically useful, you lose the ability to have the conversations that matter. You can’t discuss which bets to place if you can’t honestly discuss which futures are possible. You can’t build organizational resilience if you can’t name the things that might break you.

Beyond the Three Box Solution

So what does better look like? Not perfect, because there’s no such thing. But better.

Start by separating scenario development from strategy validation. If you’ve already decided what you’re going to do, don’t waste time pretending to explore whether you should do it. That’s fine. Not every decision requires scenario analysis. But if you’re going to do it, do it before you’ve committed, not after.

Second, make someone’s job to propose the uncomfortable scenario. Not as a pro forma exercise, but as a genuine attempt to identify the future that would most thoroughly undermine your current assumptions. This person should be rewarded for insight, not punished for negativity. In practice, this is harder than it sounds, because organizations have antibodies against this kind of thinking.

Third, test your scenarios against historical precedent, particularly from outside your industry. The future won’t be a rerun of the past, but humans consistently underestimate how much can change. What felt impossible ten years ago is ordinary now. Your scenarios should reflect that pattern, not assume you’re living in a special period of history where only incremental change happens.

Fourth, build scenarios around uncertainties that would actually change your decisions, not just your spreadsheets. If all three scenarios lead to the same strategic choice, you haven’t learned anything. The point isn’t to predict the future. It’s to identify the decision points where different futures would demand different actions.

The Courage to Be Wrong

There’s something almost philosophical at the heart of this. Scenario analysis, done well, requires accepting that you don’t know the future. Really accepting it, not just acknowledging it in a slide before proceeding as if you do.

This is threatening to organizational hierarchies built on the premise that senior people know more, have better judgment, can see further. Admitting deep uncertainty feels like admitting incompetence. So we don’t. We build models complex enough to look authoritative, but constrained enough to support our preferred narratives.

The irony is that this makes us less prepared, not more. When reality diverges from your carefully modeled scenarios, you’re forced to improvise without having done the mental preparation that genuine scenario work provides. You haven’t thought through the early warning signs. You haven’t stress tested your assumptions. You haven’t identified the points of leverage or the likely failure modes.

You’ve practiced being confident. You haven’t practiced being ready.

The View from Somewhere Else

It helps to look at how scenario thinking works in contexts where failure is immediate and visible. Military planning, for instance, takes adversarial scenarios seriously because enemies don’t care about your quarterly earnings targets. They’ll do whatever gives them advantage, including things that seem unreasonable or disproportionate by peacetime corporate standards.

Or consider how good poker players think about hand ranges. They don’t just model what they want their opponent to have. They model the full distribution of possibilities, weighted by probability, then make decisions that work across that distribution. Wishful thinking gets expensive fast when there’s actual money at stake and feedback is immediate.

The business equivalent might be: what if you had to fund your scenario planning out of your own pocket? Which futures would you still bother modeling? Which would you dismiss as unlikely? The answer probably reveals which scenarios you actually believe versus which ones you’re performing for institutional reasons.

Making It Real

None of this means scenario analysis is useless. Done honestly, it’s one of the few tools we have for structured thinking about uncertainty. It forces explicit conversations about assumptions that usually remain implicit. It creates a shared language for discussing futures that don’t yet exist.

But it only works if you’re willing to model reality, not just expectations. That means building scenarios that make you genuinely uncertain about what to do. It means including futures you hope don’t happen. It means accepting that some of your current investments might be worthless in certain plausible worlds.

It also means acknowledging what scenario analysis can’t do. It can’t predict the future. It can’t eliminate uncertainty. It can’t substitute for judgment. It can make you more prepared for more possibilities, which is valuable but less satisfying than what we usually want from it.

The hard truth is that most organizations don’t actually want better scenario analysis. They want the comforting illusion that the future is knowable and manageable. They want the strategic equivalent of a security blanket. And there’s always someone willing to provide that, wrapped in enough analytical sophistication to look like rigorous thinking.

The question is whether you’re willing to be that person, or whether you’re going to risk the awkwardness of building scenarios that actually matter. Your boss might not thank you for it. But the version of your organization that has to live in that unexpected future probably will.

Because reality doesn’t care what made it into your slide deck. It just keeps happening, indifferent to whether you were ready or not.