Table of Contents

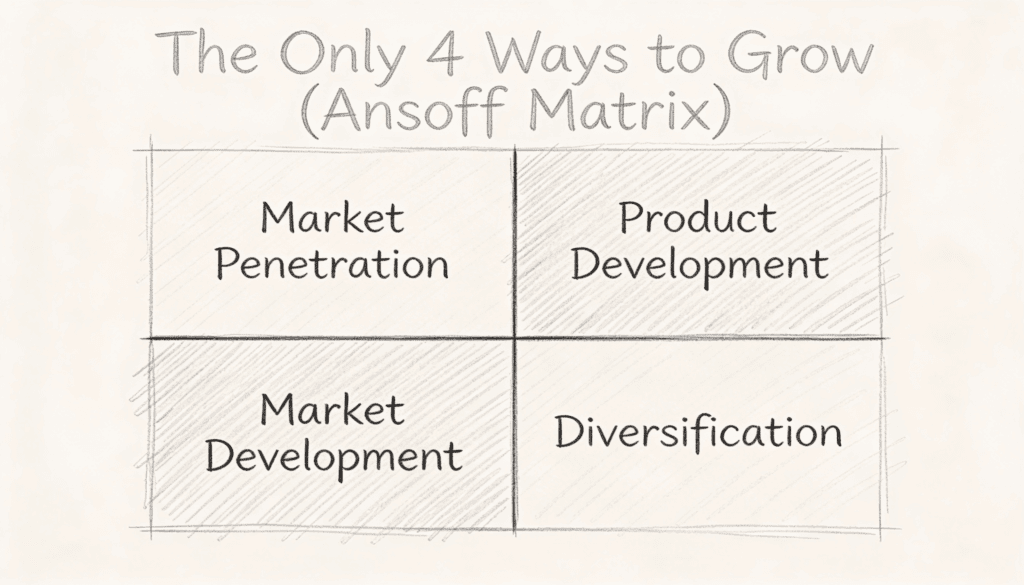

There’s something almost insulting about the Ansoff Matrix. Here’s this tidy little two by two grid, invented in 1957, claiming to capture every possible way a business can expand. Four boxes. That’s it. Your entire growth strategy, distilled into a framework so simple you could sketch it on a napkin during lunch.

And yet, like all truly useful ideas, it refuses to die precisely because it’s correct.

The matrix plots two variables: products and markets. Each can be either existing or new. Cross them, and you get four quadrants. Market penetration means selling more of what you already make to people who already know you. Product development means creating new offerings for your current customers. Market development flips that around, taking your existing products to new audiences. Diversification, the riskiest square, means venturing into entirely new products for entirely new markets.

What makes this framework endure isn’t its elegance. It’s that Igor Ansoff understood something fundamental about human nature and organizational behavior. We like to believe we’re inventing novel strategies, pioneering unprecedented paths. But strip away the jargon and the slide decks, and nearly every growth initiative fits neatly into one of these four categories. We’re not as creative as we think.

The Comfort Zone Quadrant

Market penetration sits in the top left corner, and it’s where most businesses spend most of their time. This is growth through intensity rather than exploration. You already have customers. You already have products that work. The question becomes whether you can convince people to buy more, buy more often, or convince their neighbors to start buying too.

This approach feels safe because the terrain is familiar. You know what you’re selling. You know who you’re selling to. You’ve already proven the concept. The risk here isn’t whether the fundamental model works, but whether there’s actually room left to grow within these existing boundaries.

Think of it as attempting to get more juice from an orange you’ve already squeezed. Sometimes there’s plenty left. Sometimes you’re just pressing harder on pulp. The challenge lies in knowing which scenario you’re facing, and most companies convince themselves there’s more juice available than actually exists.

The tactics here are well worn. Increase usage frequency. Encourage larger purchase sizes. Win customers away from competitors. Improve loyalty to reduce churn. None of this requires inventing anything new, which is both the appeal and the limitation. You’re optimizing a known system, hoping that optimization alone can fuel the growth you need.

What’s interesting is how many businesses treat this quadrant as though it’s unlimited. They pile resources into sales teams, marketing campaigns, and promotional offers, assuming the market will keep responding. But every market has boundaries. Customer needs plateau. Competition intensifies. At some point, you’re fighting for scraps at an increasingly expensive cost per acquisition.

The wisdom lies in recognizing when you’ve extracted most of the available value from this quadrant. Staying too long turns growth efforts into expensive exercises in diminishing returns.

The Product Gamble

Product development occupies the top right, and this is where things get more interesting. You’re sticking with the customers you know but giving them something new. The logic seems sound. These people already trust you. They’ve opened their wallets before. Why not offer them something else?

This strategy works beautifully when you truly understand what your customers need next. Apple didn’t just sell computers. They sold music players to computer buyers, then phones to music player buyers, then tablets to phone buyers. Each step felt natural because they’d built genuine insight into what their audience wanted from technology.

But here’s where most companies stumble. They assume familiarity with customers equals understanding of customers. They confuse transactional history with deep knowledge. So they launch products based on what they can build rather than what people actually need.

The other trap is relevance. Just because someone buys your coffee doesn’t mean they want you to sell them sandwiches. Brand permission is a real constraint, and it’s often invisible until you violate it. The market responds with polite indifference, and you’re left wondering why your loyal customers didn’t follow you into this logical adjacent space.

Product development also demands capabilities you might not have. Creating something new requires research, design, testing, and iteration. It strains operations. It demands different skills. The entire organization has to stretch in ways that pure market penetration never requires.

Yet when this quadrant works, it works magnificently. You leverage existing relationships and distribution while offering genuine new value. The customer acquisition cost is lower because trust already exists. You’re not starting from zero. You’re building on a foundation.

The key is honest assessment of whether you actually understand your customers well enough to know what they need next, and whether your brand has permission to deliver it.

The Audience Expansion

Market development sits in the bottom left, and it represents a different kind of bet. Same product, different people. You’ve figured out how to create value for one group, and now you’re asking whether that same value proposition works elsewhere.

Geography is the obvious version of this. A restaurant chain that succeeds in one city opens in another. A software company serving American customers expands to Europe. The product doesn’t change. The audience does.

But market development isn’t always geographic. Sometimes it’s demographic. A brand that appealed to younger consumers repositions for older ones. A business product finds consumer applications. A luxury item gets a value version for mass market appeal.

This strategy works when your product solves a universal problem or desire, and the only reason you haven’t reached other markets yet is distribution, awareness, or positioning. The underlying value is portable. It just needs translation.

The challenge is that markets differ more than we assume. What resonates in one culture falls flat in another. What works at one price point fails at another. The features that matter to one demographic are irrelevant to the next. You think you’re offering the same thing, but you’re actually asking different people to care about different aspects of it.

Market development also exposes you to competitors who already own those spaces. You’re the newcomer. They have home field advantage. The customers you’re targeting may already have established relationships and preferences. You’re not filling a void. You’re displacing someone else.

The smart approach here involves genuine curiosity about whether your core offering actually solves problems for these new audiences. Not whether you can convince them it does through marketing, but whether it genuinely does. The difference determines whether you’re expanding into opportunity or walking into a wood chipper.

The Everything, Everywhere Bet

Diversification lives in the bottom right corner, and this is where ambition meets danger. New products for new markets. You’re leaving behind everything familiar and venturing into territory where you have no experience and no existing relationships.

This is the quadrant that sounds exciting in boardrooms and terrifying in execution. The logic often goes something like this: we’ve maxed out our current opportunities, we need new engines for growth, we have capital to deploy, so let’s enter an entirely different business.

Sometimes this works spectacularly. Amazon sold books, then decided to rent computing infrastructure. Those businesses share almost nothing except the company name, and both became massive. But for every Amazon, there are countless disasters of companies that wandered into spaces they didn’t understand, bleeding resources until they either retreated or collapsed.

Diversification tends to work when there’s some hidden connection that isn’t obvious from the outside. Maybe you’ve developed a capability that applies elsewhere. Maybe you’ve identified an insight about customer behavior that unlocks a different market. Maybe you have distribution that works for multiple product categories.

But often, diversification is just a fancy word for distraction. Companies pursue it because growth in their core business has slowed, and rather than accepting slower growth or finding creative ways to reignite it, they go looking for entirely new games to play.

The risk is that you’re now competing against organizations for whom this new space is their core business. They have focus, expertise, and commitment. You have curiosity and capital. That’s usually not enough.

The other problem is that diversification splits attention and resources. The core business that funds the diversification still needs investment and leadership. But the shiny new venture consumes energy. Before long, you’re doing two things poorly instead of one thing well.

This quadrant demands the most honesty. Are you diversifying because you’ve genuinely found a compelling opportunity that leverages some real advantage you possess? Or are you diversifying because you’re bored, scared, or running from the hard work of reinvigorating what you already do?

The Real Choice Nobody Mentions

Here’s what the Ansoff Matrix reveals if you stare at it long enough. The four quadrants aren’t really equal options. They exist on a spectrum of risk and familiarity. Market penetration is lowest risk. Diversification is highest. The two middle options fall somewhere between.

But businesses rarely approach growth this way. Instead, they skip steps. They get impatient with market penetration because the gains feel incremental. They find product or market development too slow. So they jump straight to diversification, chasing the promise of dramatic expansion while ignoring the foundation they haven’t fully built.

The smarter approach is sequential. You exhaust the reasonable opportunities in market penetration. When those genuinely plateau, you move into product or market development, depending on where you see stronger opportunity. Only when you’ve actually maximized those options, not when you’re just bored with them, do you consider diversification.

This requires patience that most organizations lack. Investors want growth now. Executives have limited tenures. Everyone is optimizing for speed, and the Ansoff Matrix keeps whispering that slower, more familiar growth is often more sustainable than dramatic leaps into the unknown.

There’s also a timing element nobody discusses. Market conditions change. What worked yesterday might not work tomorrow. A market that seemed saturated might suddenly expand due to external factors. A product line that seemed tired might find new life with slight repositioning. The quadrants aren’t static destinations. They’re dynamic options that shift in attractiveness based on what’s happening around you.

The framework doesn’t tell you which quadrant to choose. It just makes explicit that you are choosing, whether you realize it or not. Every growth initiative fits into one of these boxes. The question is whether you’re choosing deliberately, with clear eyes about the risks and requirements, or stumbling into decisions because they feel exciting or seem expected.

Most strategic failures come from mismatch. The organization commits to diversification but allocates resources like it’s doing market penetration. Or it claims to focus on core markets while actually spreading itself across multiple quadrants, fully committed to none.

Why Simple Endures

The Ansoff Matrix survives because it forces clarity. In a world drowning in complex frameworks and sophisticated analysis, this little grid reminds us that growth fundamentally comes down to products and markets, and whether you’re working with what you have or reaching for what you don’t.

That simplicity is both liberating and constraining. It’s liberating because it cuts through the noise. Every pitch, every strategy, every plan can be tested against these four options. It’s constraining because it suggests limits to creativity. We’re not pioneering new territory. We’re choosing among well trodden paths.

But perhaps that’s the point. Innovation in execution matters more than innovation in strategy. The companies that win aren’t necessarily those that discover a fifth quadrant. They’re the ones that choose their quadrant wisely and execute it brilliantly.

The matrix also reveals something about human optimism and organizational delusion. We love to believe our situation is unique, our challenges unprecedented, our opportunities novel. The framework quietly insists otherwise. You’re selling something to someone. That something is either what you currently sell or something new. That someone is either who currently buys from you or someone different. Pick your combination and get to work.

There is no fifth option. No secret path the matrix missed. Just four ways to grow, each with its own risks and rewards, each demanding different capabilities and resources. The only real question is which one you’re actually built to pursue, and whether you’re honest enough with yourself to choose accordingly.