Table of Contents

We’ve built a world that worships prediction. Every boardroom wants its own crystal ball, and data science promised to deliver exactly that. Feed enough information into the right algorithms, the thinking goes, and you’ll know what customers want before they do, which products will succeed, and where your next opportunity lies.

It’s a seductive vision. It’s also dangerously incomplete.

The problem isn’t that data science doesn’t work. The problem is that knowing what will happen and knowing what to do about it are two entirely different challenges. One tells you it’s going to rain. The other builds you an umbrella, figures out where to put it, and decides whether you even need to go outside in the first place.

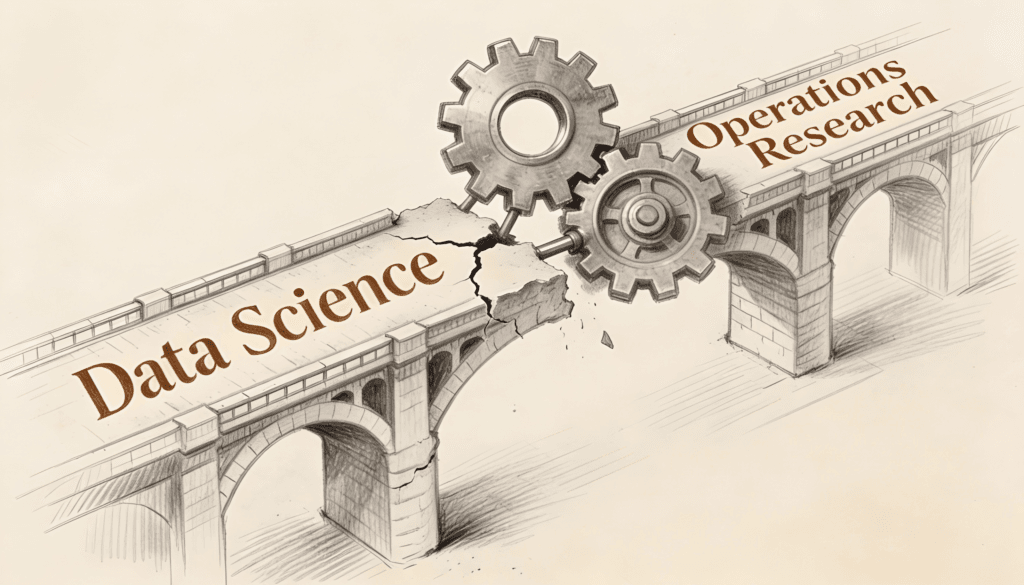

This is where operations research enters the conversation, not as a competitor to data science but as its natural complement. While everyone’s been rushing to hire data scientists, many organizations have overlooked the discipline that turns insights into decisions and decisions into action.

The Prediction Trap

Consider a retailer who has perfected demand forecasting. Their models can predict, with impressive accuracy, exactly how many units of each product they’ll sell next month. They know which stores will be busy, which days will see surges, and which items will trend. The executives are thrilled. The data science team gets bonuses.

Then reality intrudes. The warehouses are in the wrong locations. The delivery trucks follow inefficient routes. The inventory sits in places where it can’t meet the predicted demand. The staffing doesn’t match the forecasted busy periods. The accurate predictions, it turns out, didn’t come with instructions.

This is the prediction trap. We’ve become so good at seeing the future that we’ve forgotten seeing isn’t the same as doing. A weather forecast doesn’t irrigate your crops. A traffic prediction doesn’t redesign your city’s roads. Knowing what will happen matters far less than most people think if you can’t act on that knowledge effectively.

Operations research asks a fundamentally different question. Not what will happen, but what should we do. Not what patterns exist, but which choices optimize our goals. The distinction sounds subtle until you’re the one making decisions that affect real resources, real budgets, and real people.

When Insight Meets Constraint

The world runs on constraints. Every business operates within boundaries: limited budgets, finite staff, physical laws, regulatory requirements, customer expectations, competitive pressures. Data science often treats these as unfortunate complications that muddy the analysis. Operations research treats them as the entire point.

Think about airline scheduling. A data scientist might build an excellent model predicting which routes will be profitable. They might forecast demand for different times and days. They might identify customer segments and their preferences. All valuable work.

But someone still needs to figure out which planes go where, when they take off, which crews fly them, how to handle maintenance windows, what happens when weather disrupts everything, and how to recover when delays cascade through the network. That’s not a prediction problem. That’s an optimization problem operating under dozens of constraints simultaneously, many of them competing with each other.

The same pattern appears everywhere you look. Healthcare systems need to predict patient volumes, yes, but they also need to schedule surgeries, allocate operating rooms, assign staff, manage supply chains, and route ambulances. Supply chains need demand forecasts, but they also need to decide where to source materials, how much inventory to hold, which facilities to use, and how to respond when suppliers fail or costs spike.

Organizations that focus solely on prediction find themselves data rich and decision poor. They know what’s coming but not how to prepare for it. They have insights but no mechanism to translate those insights into coordinated action across complex systems.

The Architecture of Choice

Operations research emerged from a simple observation: most important decisions aren’t isolated choices but interconnected systems where everything affects everything else. Change one thing and you create ripples throughout your organization.

This systemic view stands in contrast to how many analytics teams operate. They’ll optimize marketing spend, then separately optimize logistics, then separately optimize pricing, then separately optimize workforce planning. Each analysis produces recommendations based on its own data and models. Each team declares victory.

Then senior leadership tries to implement all these optimized solutions simultaneously and discovers they conflict with each other. The marketing plan assumes distribution capabilities the logistics team can’t provide at the optimized cost. The pricing strategy works only if the workforce plan can deliver the required service levels. The whole becomes less than the sum of its parts.

Operations research thinks in systems from the start. It maps the decision landscape, identifies how choices interact, acknowledges tradeoffs explicitly, and finds solutions that work across the organization rather than in isolated pockets. This isn’t just intellectually tidier. It’s the difference between recommendations that sound good in PowerPoint and strategies that actually function in practice.

Beyond the Average

Here’s something that surprises people: average behavior often tells you almost nothing about how systems actually perform. Data science loves averages. Central tendencies, expected values, mean predictions. Operations research knows that averages kill you.

An airport might handle an average of 100 planes per hour comfortably. But planes don’t arrive on average. They arrive in clumps and clusters, with quiet periods and sudden rushes. Design your system for the average and you’ll have catastrophic failures when reality inevitably deviates from the mean.

The same logic applies to inventory. Average demand might be 100 units per day, but some days you’ll face 150 and others just 50. Stock to the average and you’ll either have costly excesses or frustrated customers half the time. Manufacturing lines, hospital emergency rooms, customer service centers: all of them live in the gaps between average and actual.

Operations research embraces variability rather than assuming it away. It plans for uncertainty, builds in buffers where they matter, and creates systems that degrade gracefully under stress rather than collapsing at the first deviation from expected conditions. This kind of resilience doesn’t come from better predictions. It comes from better design.

The Hidden Cost of Suboptimization

Organizations love to optimize things. The problem is they usually optimize the wrong things, or more precisely, they optimize things in isolation that should be optimized together.

A classic example: procurement teams get rewarded for negotiating low prices, so they source from the cheapest suppliers. Meanwhile, those cheap suppliers create quality problems that increase warranty costs, delivery delays that force expensive expediting, and longer lead times that require more inventory. The procurement team hit their numbers, but the organization spent more money.

This is suboptimization, and it’s everywhere. Sales teams maximize revenue without considering fulfillment costs. Product teams launch features without considering support burden. Finance cuts expenses without modeling how those cuts affect capacity. Everyone optimizes their piece of the puzzle while the overall picture gets worse.

Operations research forces you to define what you’re actually trying to achieve at an organizational level, then shows you how to get there even if it means some departments don’t hit their individual metrics. This makes people uncomfortable. It should. Comfort with departmental silos is often just comfort with mediocrity.

Where Algorithms Meet Reality

Data science has given us powerful tools for pattern recognition and prediction. Machine learning can find relationships in data that humans would never spot. But here’s what often gets missed: finding a pattern isn’t the same as understanding cause and effect, and understanding cause and effect isn’t the same as knowing how to intervene effectively.

A retailer might discover through clustering algorithms that certain customers buy particular product combinations. That’s a pattern. They might even predict which customers will buy those combinations in the future. That’s forecasting. But should they put those products near each other? Promote them as bundles? Adjust pricing? Change inventory policies?

The pattern doesn’t tell you what to do. You need a model of how the system responds to changes. You need to understand constraints and resources. You need optimization methods that can explore thousands of possible interventions to find ones that actually improve outcomes. You need operations research.

This matters more as systems become more complex. When you have millions of products, thousands of locations, complex supply chains, and rapid market changes, you can’t manually figure out good solutions. You need mathematical optimization to explore a solution space that’s vastly too large for human intuition or even trial and error.

The Strategy Gap

Most strategy work involves choosing between alternatives. Should we enter this market? Invest in this technology? Build this facility? Close that operation? These feel like high level decisions made through business judgment and strategic vision.

But increasingly, good strategy requires analyzing thousands of scenarios across complex systems. What happens to our supply chain if we add this production facility? How does our network perform under different demand scenarios? What’s the optimal portfolio of investments given our budget and resource constraints?

You can’t answer these questions with intuition. You can barely answer them with spreadsheets. You need the mathematical machinery that operations research provides: optimization models that can evaluate millions of configurations, simulation techniques that can test strategies under uncertainty, algorithms that can find solutions humans would never consider.

The organizations that integrate operations research into their strategic planning process make better decisions. Not because they’re smarter or have better data, but because they have tools that can actually process the complexity their decisions involve. Everyone else is essentially guessing.

The Human Element

Operations research often gets dismissed as too technical, too mathematical, too removed from the human realities of business. This criticism misses something important: properly done operations research makes space for human judgment in ways that gut instinct decision making never does.

When you build an optimization model, you’re forced to be explicit about your goals. What are you actually trying to achieve? What matters and what doesn’t? How do you make tradeoffs between competing objectives? These questions don’t have mathematical answers. They require human judgment, values, and priorities.

The mathematics lets you explore what happens if you make different judgment calls. It shows you the consequences of your priorities. It reveals hidden tradeoffs you didn’t know existed. Rather than replacing human decision making, good operations research makes those decisions more informed and more explicit.

Data alone never tells you what to optimize for. It can’t tell you whether to prioritize cost over service, growth over profitability, or short term results over long term resilience. Those are human choices. Operations research just helps you understand what those choices actually mean in practice.

Looking Forward

The gap between prediction and action won’t close on its own. As organizations collect more data and build more sophisticated models, they’ll find themselves increasingly frustrated if they can’t turn those insights into decisions and decisions into results.

The future belongs to organizations that integrate both capabilities: the pattern finding power of data science and the decision making rigor of operations research. Not as separate functions reporting to different executives, but as complementary approaches to the same goal: making better choices under uncertainty in complex systems.

This doesn’t mean every organization needs to hire operations research PhDs or build in-house optimization teams. It means recognizing that prediction is only half the puzzle, that insights need mechanisms to become action, and that the hardest problems most organizations face involve not knowing what will happen but deciding what to do about it.

The companies that figure this out will have an advantage that data science alone can’t provide. They’ll make better decisions faster. They’ll coordinate across silos. They’ll optimize what matters rather than what’s measurable. They’ll turn constraint into opportunity and complexity into competitive advantage.

Data science told us we could see the future. Operations research reminds us that we still have to build it, one optimized decision at a time.