Table of Contents

We talk about clean data like it’s rain. Clean, pure, falling from the sky into our carefully positioned buckets. The reality is messier. Data is more like oil. Someone has to drill for it, refine it, and get their hands dirty in the process.

Most companies treat analytics as a consumption problem. They want the insights without the extraction. They want the finished product without controlling the production line. This is like wanting to be a great chef while refusing to source your own ingredients. You can make something decent, but you’ll never make something extraordinary.

The supply chain metaphor isn’t accidental here. The best analytics operations mirror the best manufacturing operations. They own the means of production. They control quality at the source. They understand that excellence in the final product starts with excellence in the raw materials.

The Fantasy of Clean Handoffs

There’s a prevailing fantasy in business that specialization means separation. Marketing generates leads, sales closes them, operations delivers, and analytics measures it all. Clean boundaries. Clear handoffs. Everyone stays in their lane.

This works beautifully in theory and catastrophically in practice.

The problem is that data doesn’t respect organizational charts. When your analytics team sits three departments away from the people generating the data, you get artifacts instead of insights. You get reports on what happened two weeks ago instead of understanding what’s happening right now.

Consider what happens when a marketing team runs a campaign. They collect data in their system. Then someone exports it. Then someone else cleans it. Then someone imports it into the analytics platform. Then someone runs models on it. By the time insights emerge, the campaign is over and the team has moved on to the next thing.

Each handoff introduces friction. More importantly, each handoff loses context. The marketing team knows that half the leads came from a conference where they were giving away iPads. The analytics team just sees a spike in form submissions with suspiciously low engagement rates. Without owning the supply chain, you spend more time explaining anomalies than generating insights.

The Verticalization of Analytics

The best analytics teams I’ve encountered don’t look like analytics teams. They look like intelligence agencies embedded in every part of the business.

They have people who understand how the CRM works because they helped implement it. They have people who know why the inventory system has that weird quirk because they were there when the vendor made a mistake during installation. They have people who can tell you which sales rep always forgets to update deal stages because they sit near them.

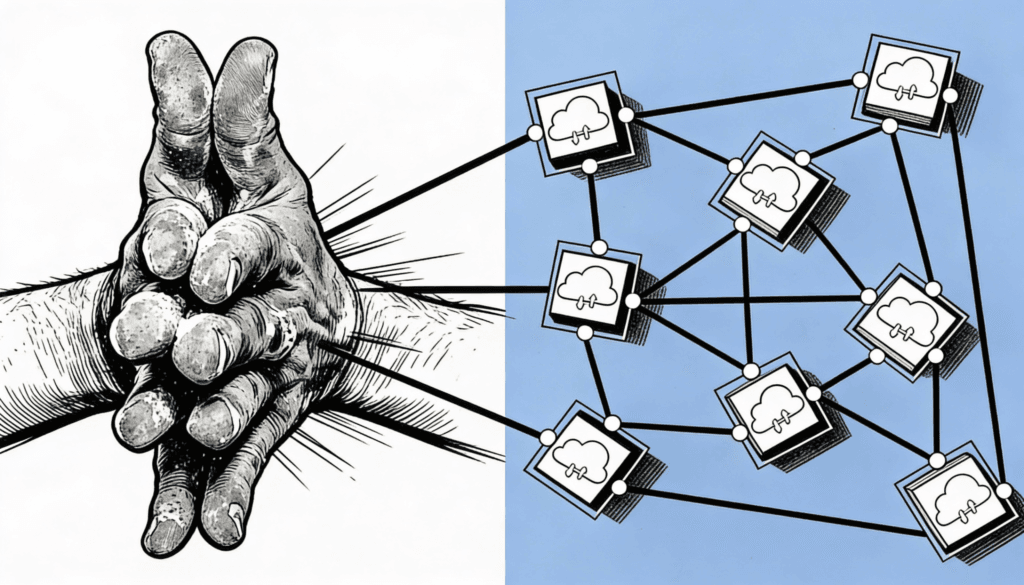

This is vertical integration for the information age. Instead of owning factories and distribution networks, you own data pipelines and collection processes. You control the supply chain from the moment a customer clicks a button to the moment an executive makes a decision based on that click.

The irony is that this approach requires less technical sophistication and more operational knowledge. The hard part isn’t building complex models. The hard part is knowing which data to trust and why some numbers look weird on Thursdays.

Quality is Made, Not Measured

There’s a persistent delusion that you can quality control your way to good data. That if you just run enough validation checks and build enough monitoring dashboards, clean data will emerge from chaos.

This is like thinking you can inspect your way to a quality product. Any manufacturing expert will tell you that quality is built into the process, not filtered out at the end.

When analytics teams own the supply chain, they design systems that generate clean data by default. They build forms that prevent bad entries. They create workflows that enforce consistency. They automate the boring stuff that humans inevitably screw up.

More importantly, they can fix problems at the source. When you notice that product codes are inconsistent, you don’t just clean them in your analytics database. You go back and fix the system that generates inconsistent product codes. When you spot that customer addresses are often incomplete, you don’t just deal with it downstream. You improve the collection process upstream.

This requires getting your hands dirty. It means leaving the comfort of your analytics platform and wading into the messy reality of operational systems. It means attending meetings about data entry procedures and caring deeply about dropdown menu options.

It sounds tedious because it is tedious. But tedium at the source eliminates chaos at the destination.

The Speed Advantage

Speed is the underrated benefit of owning the supply chain. Not just the speed of getting results, but the speed of iteration.

When analytics teams sit downstream from data collection, every question requires a ticket. Every new metric needs a meeting. Every adjustment means waiting for someone else to make a change and hoping they understand what you need.

When you own the pipeline, you move at the speed of thought. You can test a hypothesis in the morning and have results by lunch. You can spot a problem and fix it before it compounds. You can experiment with new metrics without coordinating across four departments.

This creates a compounding advantage. Faster iteration means better models. Better models mean better decisions. Better decisions mean competitive advantage.

The companies that move fastest aren’t necessarily the ones with the most resources. They’re the ones with the shortest distance between question and answer. And the shortest distance is a straight line you own end to end.

The Knowledge Moat

Here’s where things get interesting from a competitive perspective. When you own the analytics supply chain, you build institutional knowledge that’s nearly impossible to replicate.

Your team doesn’t just know what the data says. They know why it says that. They know the history. They know the exceptions. They know which customers are weird and which products have unusual characteristics.

This knowledge becomes a moat. A competitor can hire away your analysts. They can copy your dashboards. They can even replicate your models. But they can’t replicate the accumulated understanding of how your specific business generates and uses data.

This is similar to how craftspeople develop an intuition for their materials. A master carpenter knows how different woods behave. A experienced chef knows how ingredients will interact. An analytics team that owns the supply chain develops an intuition for their data that transcends what any model can capture.

That intuition is your sustainable advantage. It’s what allows you to spot opportunities others miss and avoid mistakes others make.

The Control Paradox

There’s a paradox in all of this. The more control you have over the supply chain, the less you need to exercise that control.

When systems are designed well from the start, they run smoothly. When data collection is built correctly, it produces clean outputs. When processes are automated intelligently, they require minimal intervention.

The investment in control is frontloaded. You spend time upfront designing systems, building pipelines, and establishing processes. But once that foundation exists, everything gets easier.

This is the opposite of how most organizations approach analytics. They underinvest in infrastructure and then spend forever firefighting. They treat each analysis as a custom project instead of building systems that make analysis trivial.

The teams that own their supply chains aren’t constantly busy. They’re strategically idle. They’ve automated the routine so they can focus on the novel. They’ve systematized the predictable so they can explore the uncertain.

The Human Element

None of this works without people who understand both strategy and data plumbing.

The analytics professionals who thrive in this model aren’t just technical experts. They’re translators who can move between the abstract world of business strategy and the concrete world of database schemas. They can discuss market positioning in the morning and debate data normalization approaches in the afternoon.

These people are rare. Most people specialize in one domain or the other. But when you find someone who can bridge both worlds, they become incredibly valuable. They can see how a strategic decision affects data collection and how data quality affects strategic options.

Building a team like this requires hiring differently. You need people who are curious about operations, not just analysis. People who want to understand how things work, not just what the numbers say. People who are willing to get their hands dirty.

The Strategic Implication

Owning the analytics supply chain changes what’s possible strategically.

It allows you to make decisions faster than competitors. It enables experimentation that would be too expensive if you had to coordinate across multiple teams. It creates the foundation for automation that seems impossible with fragmented data systems.

More subtly, it changes how you think about competitive advantage. When your analytics infrastructure is solid, you can compete on speed and adaptability rather than just scale. You can personalize when others batch process. You can respond when others report.

This matters increasingly as markets move faster. The advantage goes to organizations that can sense and respond quickly, not just those that can accumulate and analyze slowly.

Building this capability doesn’t happen overnight. You can’t restructure your entire organization around analytics principles tomorrow. But you can start small. Pick one critical data pipeline and own it end to end. Build it right. Automate it thoroughly. Make it a model for what’s possible. Then expand. Take on another process. Integrate another system. Gradually extend your control over the information supply chain.

The key is being patient with the process but impatient with quality. Don’t accept workarounds. Don’t tolerate technical debt. Don’t settle for “good enough” when the foundation is still being laid.

Each piece you control makes the next piece easier. Each system you improve makes improvement easier. The effort compounds.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here’s what makes this difficult: owning the supply chain requires admitting that analytics isn’t a separate function. It’s woven into operations. It’s part of how work gets done, not a retrospective on work that’s been completed.

This threatens traditional organizational structures. It blurs boundaries. It requires people to expand their roles and learn new skills.

But the alternative is worse. Without ownership of the supply chain, analytics remains a reporting function. It can tell you what happened but can’t help you change what happens next. It can measure outcomes but can’t influence processes.

The companies that embrace this uncomfortable truth gain an edge. They build analytics operations that aren’t just smarter but faster and more adaptable. They create feedback loops that accelerate learning and improvement.

The Real Prize

The ultimate goal isn’t cleaner data or faster reports. It’s better decisions made more often.

When you own the analytics supply chain, decision making shifts from periodic and centralized to continuous and distributed. People throughout the organization can access reliable information and act on it. They don’t need to wait for reports or request analyses.

This democratization of insight is only possible with a robust supply chain. Without it, you’re stuck rationing access to analytics resources and creating bottlenecks around data experts.

With it, you create an organization that learns from every interaction, improves every process, and adapts every day.

That’s the real prize. Not clean data for its own sake, but an organization that gets smarter faster than its competition.

The dirty hands are just the price of admission.