Table of Contents

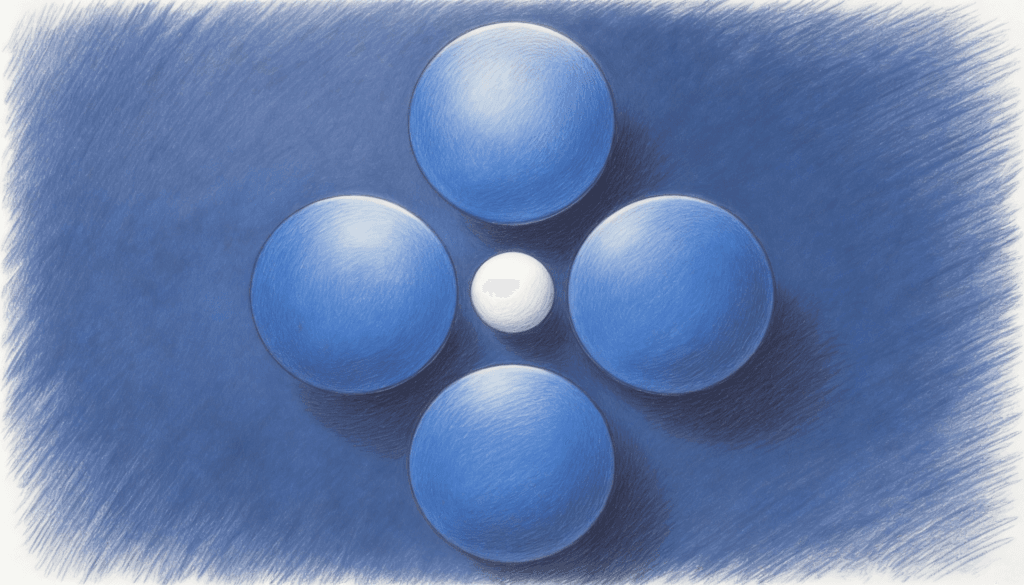

The McKinsey consultants walk into the conference room with their deck. Slide three reveals a pyramid. Slide seven shows three perfectly non-overlapping circles. Slide twelve presents four neat boxes that somehow contain all possible outcomes of a $2 billion decision. Everything is MECE. Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive. Nothing overlaps, nothing escapes.

The client nods. The framework feels solid. It feels complete. It feels wrong.

Here’s what nobody tells you about MECE thinking: it’s a cage dressed up as a methodology. Yes, it brings order. Yes, it makes communication cleaner. But order and truth are not the same thing. Sometimes the mess is the message.

The Seduction of Clean Categories

MECE promises something irresistible. It says you can take any complex problem, any tangled reality, and sort it into boxes that don’t overlap and don’t leave gaps. The world becomes a Venn diagram with perfect boundaries. Marketing sits over here. Operations lives over there. Never shall they touch.

This works beautifully in textbooks. In real organizations, marketing decisions shape operational capacity. Operational constraints reshape marketing strategy. The boundaries blur. The categories leak into each other like watercolors in rain.

But we keep drawing the boxes. We keep pretending the categories hold. Because the alternative feels dangerous. If we admit that customer segments overlap, that strategic priorities conflict, that our neat frameworks can’t capture reality, what then? We might have to think harder. We might have to sit with ambiguity.

MECE thinking trains us to see the world as separable. Pull this lever, that outcome follows. Adjust this variable, this metric moves. Cause and effect occupy different boxes. The problem is that most interesting questions live in the overlaps we’ve declared illegal.

Where Messiness Wins

Consider innovation. Everyone wants it. Few achieve it. One reason? Innovation happens at intersections that MECE thinking teaches us to avoid. The smartphone wasn’t born in the “phone” category or the “computer” category. It emerged from their collision. The boundaries had to blur before something new could form.

Or take customer behavior. A MECE framework might divide customers into segments: price sensitive, quality focused, convenience driven. Clean. Distinct. Wrong. Real customers are price sensitive on Tuesdays and quality focused on Thursday next month. They want convenience but will wait for craftsmanship. They contain multitudes. They refuse to stay in their boxes.

The strategist who insists on MECE frameworks for customer segmentation will create elegant presentations. The strategist who accepts messiness will understand actual humans.

This matters more as problems get complex. Simple problems reward clean categorization. Complicated problems tolerate it. Complex problems laugh at it. In complex systems, everything touches everything else. Feedback loops spiral. Second order effects dwarf first order effects. The boxes we draw become fictional boundaries imposed on an indifferent reality.

The Tyranny of Completeness

The “collectively exhaustive” part of MECE carries its own trap. It promises completeness. It suggests that if you just think hard enough, draw enough boxes, you can capture the whole picture. Nothing will escape. Every possibility will find its home.

This is how strategic planning becomes an exercise in elaborate delusion. Teams spend weeks ensuring their framework covers every conceivable scenario. They achieve collective exhaustiveness. They’ve missed the point entirely.

The future doesn’t care about your categories. It will arrive through the gaps in your framework. The most important opportunities and threats often emerge from places your taxonomy never thought to include. Black swans don’t announce themselves with a category label.

Nassim Taleb noticed this. The events that reshape industries, nations, and lives tend to be the ones nobody put in a box. Not because people weren’t smart enough to imagine them, but because the human mind rebels against truly exhaustive thinking. We satisfice. We create frameworks that feel complete. Then we stop looking.

A messy approach accepts incompleteness from the start. It says: here are the patterns I see, the dynamics I notice, the forces that seem important. But I know I’m missing things. The framework is a map, and maps lie by omission. This intellectual humility beats false confidence every time.

When Clean Becomes Stupid

Mutual exclusivity sounds sophisticated. It prevents double counting. It eliminates ambiguity. It also eliminates truth when categories genuinely overlap.

Is remote work a technology issue or a culture issue? Yes. Is customer churn a product problem or a service problem? Yes. Is organizational performance about strategy or execution? If you pick one, you’ve already lost.

The real world runs on overlapping categories. A cost saving initiative might also be a quality improvement and a morale booster and a competitive advantage. Insisting these must be separate prevents us from seeing the leverage point that affects all of them.

This isn’t just philosophical. It shapes decisions. When frameworks demand mutual exclusivity, organizations create silos. The marketing team owns customer satisfaction. The product team owns innovation. The operations team owns efficiency. Nobody owns the spaces between, which is where most value hides.

Companies that break through this limitation often do it by accident. Someone notices that the overlap everyone ignored contains the actual opportunity. The “hybrid” category that violated MECE principles turns out to be the future. But they discover this despite their frameworks, not because of them.

The Consultant’s Dilemma

MECE thinking persists partly because it serves consultants brilliantly. It makes recommendations seem rigorous. It structures presentations clearly. It gives clients the impression that someone has thought of everything.

This isn’t cynical manipulation. Most consultants believe in the frameworks they use. They’ve been trained in them. They’ve seen them work. And they do work, for a certain class of problems. Restructuring a supply chain. Evaluating acquisition targets. Optimizing a cost structure. These benefit from clean categorization.

But consultants face an incentive problem. Messy analysis is harder to sell. It’s harder to present. It resists neat conclusions. The client asks: what should we do? The messy answer is: it depends on how these seven factors interact, and we can’t fully predict their interaction, so here’s a portfolio of experiments to run. The MECE answer is: do these three things in this order. Guess which one sounds more confident?

Confidence sells. Nuance doesn’t. So the frameworks get cleaner. The categories get sharper.

Living in the Overlap

What does embracing messiness actually mean? It doesn’t mean abandoning structure. It means choosing structure that matches reality rather than structure that matches our desire for simplicity.

Network thinking helps. Instead of boxes with boundaries, imagine nodes with connections. Customer segments aren’t discrete categories but clusters in a continuous space. Strategic priorities aren’t separate items on a list but interconnected objectives with complex relationships.

This shift feels subtle but changes everything. In box thinking, you optimize each category independently. In network thinking, you look for leverage points where a single change cascades through multiple areas. You hunt for the overlaps that MECE thinking made invisible.

Scenario planning offers another path. Instead of trying to categorize every possibility exhaustively, you sketch a few distinct futures and explore how your strategy performs in each. You accept that you haven’t covered everything. You focus on robustness instead of completeness.

Or consider design thinking’s emphasis on prototyping. Rather than analyzing your way to the perfect categorization, you build something messy and learn from it. The prototype violates all kinds of clean boundaries. That’s the point. It reveals interactions you couldn’t have anticipated.

The Meta Problem

Here’s the irony: this article has presented a framework. MECE versus messy. Two approaches, seemingly mutually exclusive. I’ve done the thing I’m critiquing.

Maybe the real insight is knowing when to use which lens. MECE thinking works when you need clarity quickly. When you’re communicating to a broad audience. When the problem actually does have clean boundaries. When precision is better than no structure at all.

Messy thinking works when accuracy matters more than elegance. When you’re early in understanding a problem. When the interactions between categories contain crucial information. When you need innovation more than optimization.

The mistake is believing one approach is always superior. The discipline is choosing appropriately.

Why We Reach for the Boxes

There’s a deeper reason MECE thinking persists. Ambiguity creates anxiety. Overlapping categories feel unstable. Incomplete frameworks seem unfinished. Our minds crave closure. We want problems solved, not explored. We want answers, not better questions.

MECE frameworks satisfy this craving. They provide intellectual closure. They let us feel we’ve mastered the problem. This feeling is often an illusion, but it’s a comforting illusion.

Messy thinking requires comfort with discomfort. It means presenting analysis that feels unfinished because it is unfinished. It means admitting that some important things can’t be cleanly categorized. It means leadership that can hold ambiguity without rushing to premature clarity.

This is hard. Especially in organizational cultures that reward decisiveness and punish uncertainty. But it’s increasingly necessary. As problems get more complex, as change accelerates, as systems become more interconnected, the gap between clean frameworks and messy reality widens.

What This Means for You

If you’re building strategy, audit your frameworks. Where have you imposed mutual exclusivity on things that actually overlap? Where are you claiming completeness while ignoring important gaps? Where does your clean structure obscure crucial interactions?

Try this: take your most important strategic framework. The one you use to make big decisions. Now deliberately violate it. Create a hybrid category that breaks the mutually exclusive rule. Explore a scenario that falls outside your collectively exhaustive boxes. See what emerges.

If you’re analyzing data, resist the urge to force everything into predefined categories. Let some observations remain ungrouped. Look for the outliers that don’t fit. They often contain the signal while your neat categories contain the noise.

If you’re leading a team, notice when clean categorization shuts down thinking rather than enabling it. When someone says “that’s a marketing question, not an operations question,” you’ve just witnessed a box blocking insight. The interesting answer might require both lenses simultaneously.

The Paradox

The ultimate paradox of MECE thinking is that it often fails to be collectively exhaustive while insisting on mutual exclusivity. It claims completeness but achieves tidiness. It promises structure but delivers partial blindness.

Messy thinking, by contrast, admits its limitations but often sees more. It accepts overlap and incompleteness but navigates complexity better. It violates the rules of good frameworks and produces better understanding.

Perhaps the real choice isn’t between MECE and messy. It’s between admitting messiness or pretending it away. Reality is messy. Our frameworks can acknowledge this or fight it. One leads to learning. The other leads to confident ignorance dressed in good PowerPoint.

The boxes will always be there, ready to organize our thinking. The question is whether we let them organize away the truth. Whether we choose the comfort of clean categories over the discomfort of accurate understanding. Whether we optimize for elegance or insight.

Most of the time, we can’t have both.

Choose wisely.

Pingback: Why Your data "Deep Dive" Feels Like Drowning to Your Boss